This blog post accompanies the SDPB Monday Macro segment that airs on Monday, April 29, 2024. Click here to listen to the show, which begins at minute 21:30. For more macroeconomic analysis, follow J. M. Santos on Twitter @NSMEdirector.

In the global financial system, the U.S. dollar enjoys an exorbitant privilege, or so say the French, who coined the term—privilège exorbitant—in relation to the U.S. currency in the 1960s. The privilege exists because the U.S. dollar is a so-called international reserve currency, a store of international value other countries hold in relatively large quantities to settle international transactions between sovereigns, for example. Consequently, U.S. balance-of-payments imbalances—think, persistent U.S. trade deficits, for example—do not weaken the international exchange value of the U.S. dollar the way such imbalances might weaken non-reserve currencies. The U.S. dollar is sought after around the world in ways that effectively place a floor beneath its foreign-exchange value.

While the dollar has enjoyed its exorbitant privilege since the middle of the twentieth century, the currency is having a particularly popular moment, thanks in large part to the Federal Reserve, which has implemented a contractionary monetary policy likely to last longer than most observers had expected. Higher (interest rates) for longer is the new mantra. (New, that is, to those who do not listen to Monday Macro). In the words of the Economist magazine, The greenback’s back. This is to say, despite inflationary pressures—and, thus, falling domestic purchasing power of the dollar—at home, the international purchasing power of the dollar is rising. Along with a strengthening dollar comes the risks of trade wars, in which China is likely to be the primary target, particularly if a second Trump administration has anything to say about it.

Wait, what? Tight monetary policy insights trade wars?

Yes, but it only works in practice.

To understand the connection between relatively tight monetary policy—think, relatively high U.S. interest rates in a relatively strong economy—and an impending trade war with China, let’s begin with foreign-exchange markets, which determine foreign-exchange rates.

A foreign-exchange rate—hereafter, an exchange rate—is the price of one currency in terms of another. For example, around the time this blog post published, the price of a U.S. dollar in terms of the British pound was £0.79 per U.S. dollar; or, put differently, the price of a British pound in terms of the U.S. dollar was $1.26. Quoting either relative price—£0.79 per U.S. dollar or $1.26 per British pound—is correct, of course. To be consistent throughout this blogpost, I quote the exchange rate as the foreign-currency price of the domestic currency: for example, I use £0.79 per U.S. dollar as opposed to $1.26 per British pound.

The British-pound price of a dollar is determined by the demand and supply for each currency in the wholesale foreign-exchange market, where financial institutions buy and sell various currencies—or, more precisely, where financial institutions buy and sell bank accounts denominated in various currencies. This is to say, the British-pound price of the U.S. dollar is determined in a so-called flexible-exchange rate regime. Generally speaking, an exchange-rate regime refers to the institutional rules of the game that governments set unilaterally or multilaterally to determine how economic agents—individuals, corporations, and so on—in their respective countries engage in international financial transactions and, thus, determine exchange rates.

Currencies that trade in entirely unfettered markets are so-called free-floating currencies, which include the British pound, the euro, the Japanese Yen, the US dollar, and about twenty other so-called hard currencies. Other types of exchange-rate regimes include intermediate regimes, in which a government pegs—or, in other words, sets—the time path of the foreign-exchange value of its currency, and hard-peg regimes, in which a government essentially adopts a foreign currency. The euro is a particularly interesting example of a hard-peg regime within the twenty countries that have adopted the euro, which floats freely in a flexible-exchange rate regime outside the euro area. For example, within the euro area, the euro in Spain is identical to the euro in Germany: a hard peg of 1 euro in Spain = 1 euro in Germany exists; however, the euro price of, say, the U.S. dollar is determined by the demand and supply for each currency in a flexible-exchange rate regime. Regime choice—that is, why a country establishes one regime over another—is quite nuanced and complicated.

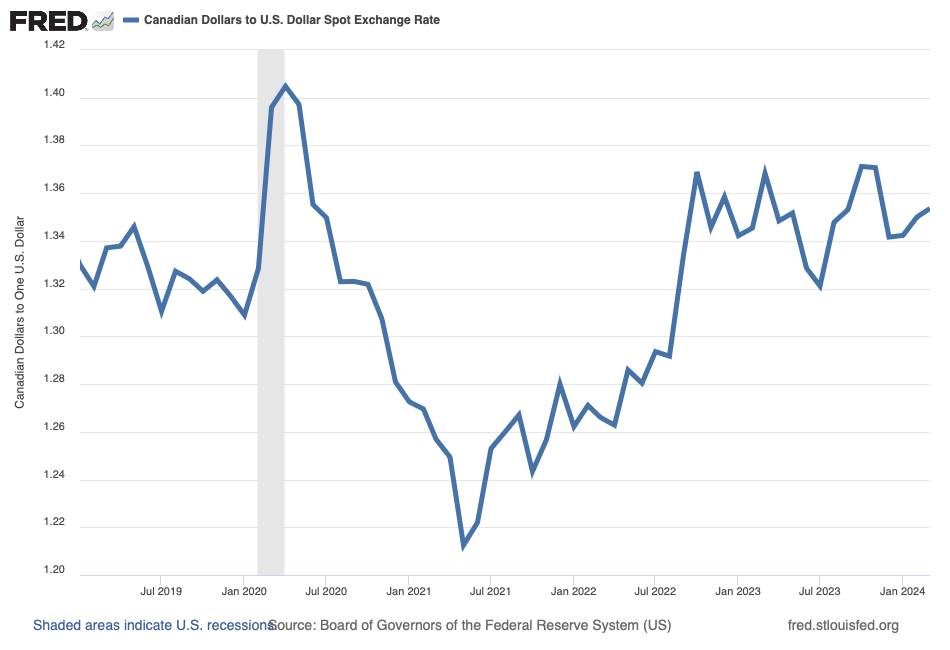

In Figure 1, I illustrate, for example, the free-floating exchange rate between the Canadian dollar and U.S. dollar; thus, a vertical-axis reading of, say, 1.36 in Figure 1 means the Canadian-dollar price—think, foreign-currency price—of the dollar is 1.36 Canadian dollars.

According to Figure 1, the Canadian-dollar price of the US dollar has generally increased over the last three years, an observation we glean from Figure 1 where the exchange rate I illustrate rises from about mid-2021 to the present. Most importantly for the purposes of this blog post and in relation to the Economist article to which I referred earlier, the pound price of the US dollar has risen suddenly and substantially in just the last year or so; and this pattern is typical of other foreign-currency prices of the US dollar as well. For example, the same Economist article reports the Indian rupee, Mexican peso, Chinese yuan, British pound, euro, and Japanese yen have each weakened relative to the U.S. dollar since the start of 2024.

Why do exchange rates move over time?

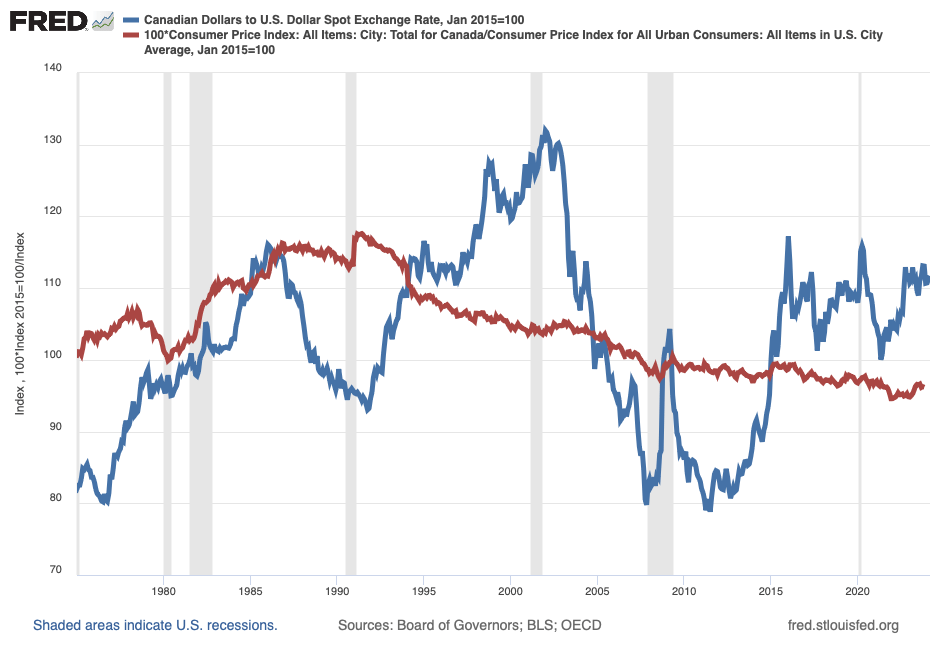

In general, how macroeconomists model and, thus, explain exchange-rate movements over time depends on the length of time we are studying. To explain exchange-rate movements over the long run—over the span of several years, for example—economists draw on the theory of purchasing-power parity. The theory rests on the strong but instructive assumptions that goods and services produced in each country are identical and trade freely between countries. The principal implication of these assumptions is that, in the long run, nominal exchange rate movements between any two currencies—such as the Canadian and U.S. dollars I illustrate in Figure 1, for example—are governed by the average price levels in the countries that use the currencies. For example, over the long run, the nominal exchange rate between the Canadian dollar and the U.S. dollar converges to the ratio of the average price levels of goods and services in Canada and the United States. To demonstrate purchasing-power parity, in Figure 2, I illustrate the Canadian dollar nominal exchange rate (in blue; I illustrate the series in Figure 1 over a shorter time frame), along with the ratio of average price levels—think, consumer price indices—in Canada and the United States.

In Figure 2, the pattern the theory of purchasing-power parity implies is evident. This is to say, over the relatively long span of nearly five decades, the nominal exchange rate (blue) reverts to—or, less formally, moves around—the ratio of average price levels (red). To understand why, consider the late 1990s, when the U.S. dollar generally appreciated relative to the Canadian dollar (and so the blue line rose); the appreciation was real, as well as nominal, because the nominal exchange rate rose above the ratio of average price levels: the purchasing power of the U.S. dollar exceeded the purchasing power of the Canadian dollar. In the parlance of international macroeconomics, by the early 2000s, the U.S. dollar was overvalued against the Canadian dollar. The terms of trade incentivized Americans and Canadians to purchase Canadian goods and services, eventually increasing the value of the Canadian dollar and, in doing so, eventually moving the nominal exchange rate back toward the ratio of average price levels—the blue line returned to the red line around 2005—(re)establishing purchasing power parity. Indeed, the theory of purchasing power parity underlies the longstanding Big-Mac Index—based on an internationally homogenous good of two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, and onions on a sesame-seed bun—that the The Economist magazine introduced in 1986 as a (lighthearted) measure of exchange-rate purchasing-power parity.

The (long-run) theory of purchasing-power parity cannot explain exchange-rate movements over a few years, which, in the context of international macroeconomics, qualifies as the short run. To explain exchange-rate movements over the short run, economists draw on the theory of interest-rate parity, which rests on the strong but instructive assumptions that country-specific risks assumed by investors—think, savers who buy financial assets in different countries and, thus, different currencies—are the same across countries, and financial capital flows freely around the world (so investors can freely enter and exit any financial market in any part of the world).

The principal implication of the interest-rate parity assumptions is that, in the short run, nominal exchange rate movements between any two currencies are governed by the returns available in the two countries—think, the difference between the interest rate paid on a treasury bond in each country—and the expected (short-term) movement of the exchange rate. For example, suppose the interest rate in the United States and the interest rate in Canada are each 2 percent, and suppose investors do not expect the exchange rate between the two currencies to change anytime soon; thus, in this case, interest-rate parity exists: whether you invest your money in the U.S. or in Canada, you earn a 2-percent return. Now, suppose the interest rate in the U.S. rises to 5 percent, while the interest rate in Canada remains at 2 percent. In this case, the Canadian dollar must depreciate (by about 3 percent) against the U.S. dollar, creating an expected Canadian-dollar appreciation (of about 3 percent) that compensates investors who invest in the Canadian dollar for the lower interest rate on Canadian-dollar denominated assets—again, think treasury bonds, for example. Thus, according to the theory of interest-rate parity, all else equal, differences in interest rates govern short-term movements in exchange rates.

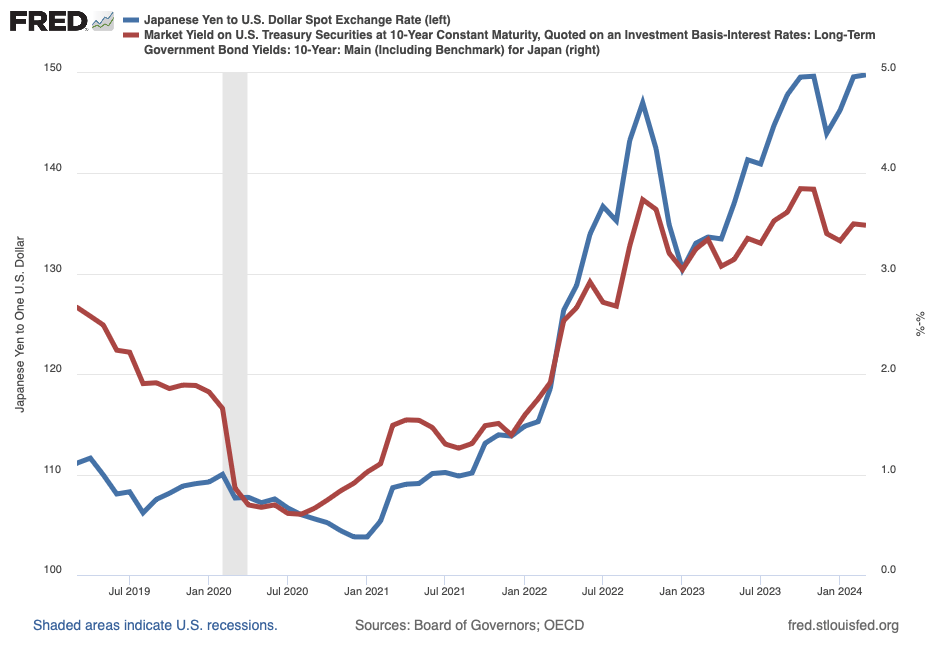

To demonstrate interest-rate parity, in Figure 3, I illustrate the Japanese yen / U.S. dollar nominal exchange rate (in blue), and the difference in 10-year treasury yields—long-run, risk-free interest rates, essentially—in the two countries (in red).

According to Figure 3, the 10-year yield to maturity in the U.S. has risen above its corresponding yield to maturity in Japan, in this case because the Federal Reserve has aggressively tightened monetary policy, while the (central) Bank of Japan has not. Consequently, the yen has depreciated—and, in turn, the dollar has appreciated—so the expected appreciation of the yen compensates investors in the yen for the difference in interest rates in the two countries. This is to say, the yen price of the U.S. dollar is positively correlated with the difference between interest rates in the U.S. and Japan: the blue and red lines in Figure 3 move together. More generally, then, the interest-rate differential—and, thus, the theory of interest-rate parity—essentially explains why the dollar is strong relative to the yen and several other currencies at the moment.

Exchange rates beget trade wars

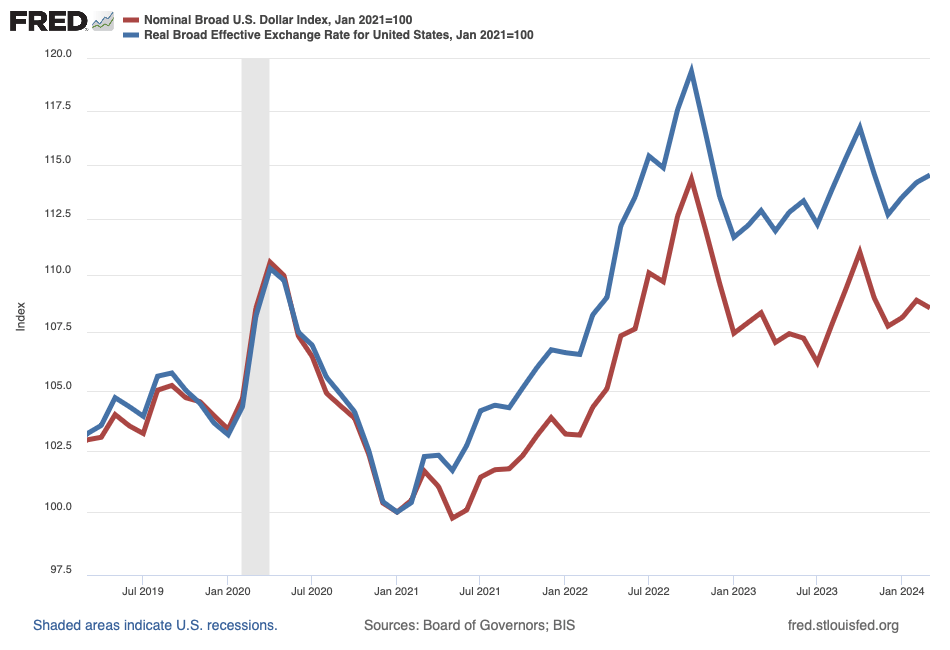

Because exchange rates move quickly over time while average price levels, such as those I illustrate in Figure 2 (in red), move slowly over time, in practice a nominal exchange-rate appreciation implies a real-exchange rate appreciation: when the dollar strengthens in nominal terms relative to other currencies, the dollar strengthens in real terms as well because the average price level in each country takes a relatively long time to adjust. I demonstrate this pattern in Figure 4, in which I illustrate nominal and real foreign-exchange values of the U.S. dollar against a basket of currencies—an average foreign-exchange value of the U.S. dollar, essentially.

According to Figure 4, as the nominal foreign-exchange value of the U.S. dollar has risen, so too has its real value, meaning the international purchasing power of the U.S. dollar has risen as well. In the short run, all else equal, a rise in the international purchasing power of the U.S. dollar tends to cause U.S. imports to increase—because from the perspective of American shoppers imports are relatively inexpensive—and U.S. exports to decrease—because from the perspective of foreign shoppers U.S. exports are relatively expensive. Put differently, then, in the short run, a rise in the international purchasing power of the U.S. dollar tends to increase (in absolute value) the U.S. trade deficit, an outcome that troubles some observers, though not international macroeconomists, who tend to be trade-deficit agnostic. (I maintain a persistent trade deficit with the individual who cuts my hair, an outcome over which I have not lost a wink of sleep; trade-deficit agnosticism is generally sound economics.)

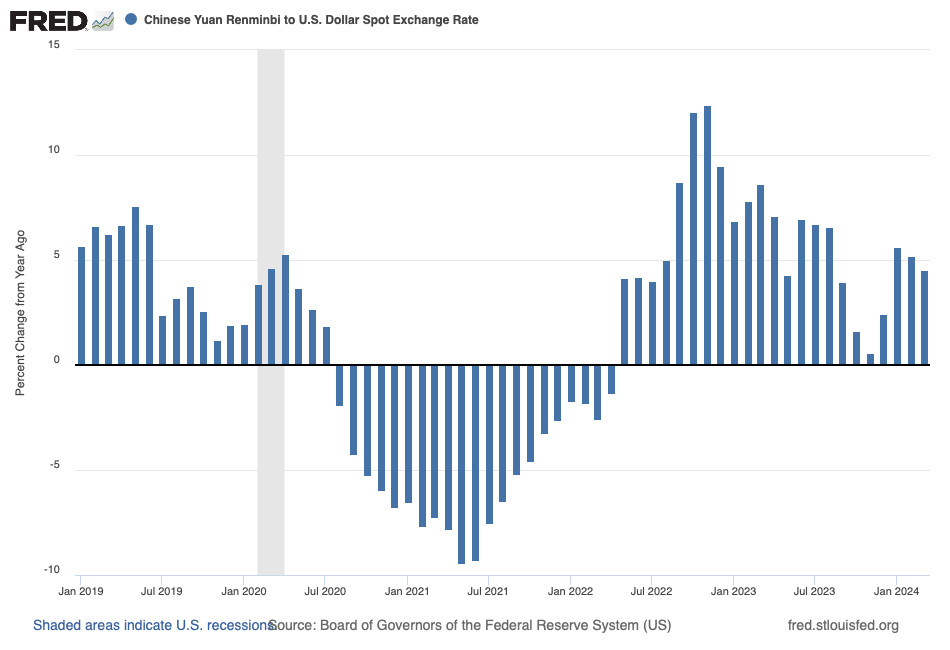

Enter China, the country with which the U.S. maintains its largest trade deficit. The recent strength of the U.S. dollar has occurred relative to the yuan as well. In Figure 5, I illustrate this pattern with a bar chart; the height of each bar measures the year-over-year percentage increase in—think, appreciation of—the U.S. dollar relative to the yuan.

According to Figure 5, against the yuan, the U.S. dollar has strengthened consistently since June 2022. All else equal, the U.S. dollar nominal appreciation increases the purchasing power of the U.S. dollar relative to Chinese goods and services, pressuring the U.S. trade deficit with China to grow (in absolute value). To be sure, saving and investment patterns within a country, as opposed to foreign-exchange value patterns between countries, ultimately determine trade deficits. But it doesn’t matter. The strength of the dollar and, thus, the weakness of the yuan will prove to be a political football. Accusations of currency manipulations—specifically, accusations that China artificially weakens the yuan—cannot be far behind.