This blog post accompanies the SDPB Monday Macro segment that aired Wednesday, January 8. Click here to listen; the segment begins the SDPB program, In the Moment.

Last weekend, I visited San Francisco to attend the annual three-day meeting of the American Economic Association (AEA), which meets in conjunction with 66 associations in allied disciplines known as the Allied Social Science Associations (ASSA). The meeting consists largely of presentations of research across all fields in economics. According to the AEA website, the meeting assembles, “The best minds in economics…to network and celebrate new achievements in economic research.” Thus, for three days in San Francisco, giants roamed among me. I attended presentations (on macroeconomics, monetary policy, and financial regulation, for the most part), took copious notes, and flew home reflecting on takeaways; I settled on two in relation to macroeconomics.

- Inflation, like poison, is all about the dose.

In a panel discussion titled, “Inflation and the Macroeconomy,” Ben Bernanke (The Brookings Institution), John Cochrane (The Hoover Institution), Jason Furman (Harvard Kennedy School), and Christina Romer (University of California-Berkeley) discussed what caused and what we learned from the relatively high post-pandemic inflation we experienced. The panelists disagreed somewhat about what caused the inflation: for example, did an aggregate supply shock accommodated, sensibly or otherwise, by monetary policy cause the inflation? Or did an aggregate demand shock driven by (excessively) expansionary fiscal and monetary policies and the expectation of an effective (inflation-induced) Treasury debt default cause the inflation?

The panelists agreed the profession—and, as a practical matter, economic policymakers and politicians—lost sight of how pernicious inflation is to the average consumer. Unlike, say, unemployment, which most labor force participants do not experience at a moment in time, everyone who shops experiences inflation—a fall in the purchasing power of money, independent of the goods and services money buys. An unemployment rate of 4 percent implies 96 percent of the labor force has not lost their jobs; whereas an inflation rate of 4 percent implies 100 percent of consumers have lost 4 percent purchasing power. Moreover, to consumers, the frequency of purchases of a good or service that sells for a higher price because of inflation instigates a level of frustration over inflation that is disproportionately large relative to the share of income the consumer spends on the good or service: because I purchase eggs often, purchasing eggs reminds me often of the perniciousness of inflation, even though I spend a small share of my income on eggs, for example.

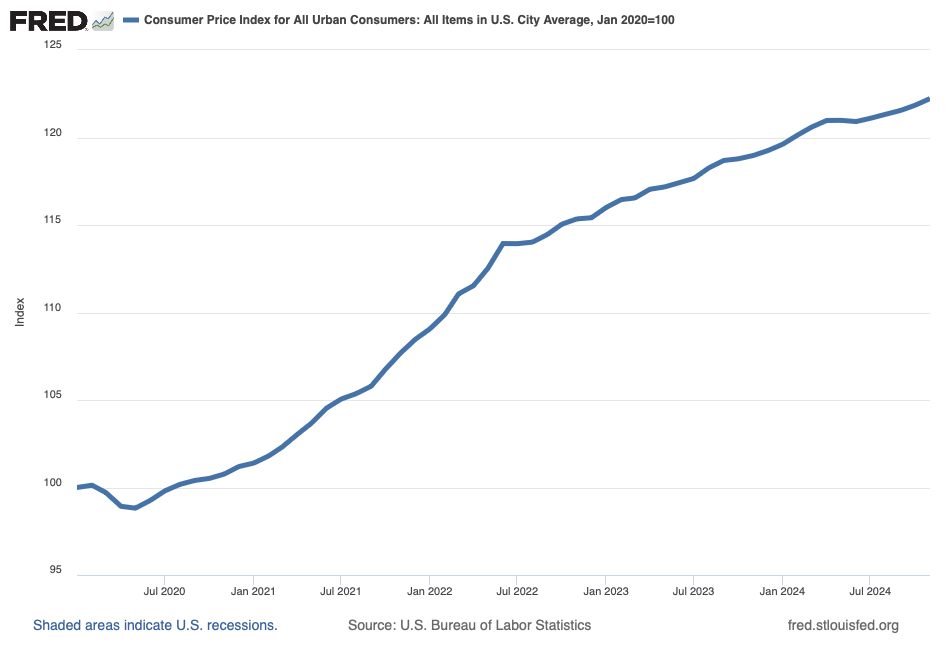

The profession also lost sight of how the public—read, the public not trained in economics—thinks about inflation, which is the growth rate in the average price level. In Figure 1, I illustrate the consumer price index—a measure of the price level as opposed to the inflation rate—since January 2020; I scale the series so the observation for January 2020 equals 100.

According to Figure 1, on average, a good or service a consumer purchased in January 2020 for, say, $100 rose to $122 by November 2024, a 22 percent increase in the average price level. Meanwhile, in November 2024, the year-over-year inflation rate—the annual growth rate in the price level illustrated in Figure 1 for November 2024—registered 2.7 percent.

Not surprisingly, the public is more aware of and concerned about the prices of goods and services than the growth in the average price level; thus, to the general public, achieving low and stable inflation—targeting the inflation rate, as it were—is less meaningful than achieving stable prices. Similarly, celebrating the return of inflation to near 2 percent annually rings hollow with consumers who pay on average 22 percent more for goods and services now compared to 2020. Put differently, it’s tough to get excited about a relatively modest 2.7 percent inflation rate when the average price level is 22 percent higher than it was just before the pandemic.

The years of low and stable inflation around 2 percent prior to the pandemic lulled economists into a false sense of comfort that relatively high inflation was a thing of the past; ostensibly, this time was different, except it wasn’t—expansionary monetary policy would not stoke inflation, except it did. Gains in the labor market prior to the pandemic, when the rate of unemployment reached an astoundingly low 3.5 percent, absent relatively high inflation, instilled in much of the economics profession a dovish perspective that emphasized real outcomes—think a lower unemployment rate—over nominal outcomes—think, a lower inflation rate—even though in theory monetary policy has lasting effects on nominal outcomes, only.

- Monetary policy, much of it activist, is here to stay.

In a panel discussion titled, “Monetary Policy,” Mary C. Daly (President and CEO, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco), Karen Dynan (Harvard University), Adriana D. Kugler (Federal Reserve Board of Governors), and John B. Taylor (Stanford University) discussed the appropriate framework for monetary policy—the strategy, goals, and operational tactics the central bank uses to achieve its mandate of, say, full employment and low and stable inflation in the case of the Federal Reserve System. Essentially, the discussion centered on whether a monetary policy rule—a (John) Taylor rule for example—or monetary policy discretion is most appropriate in the aftermath of the post-pandemic inflation and otherwise.

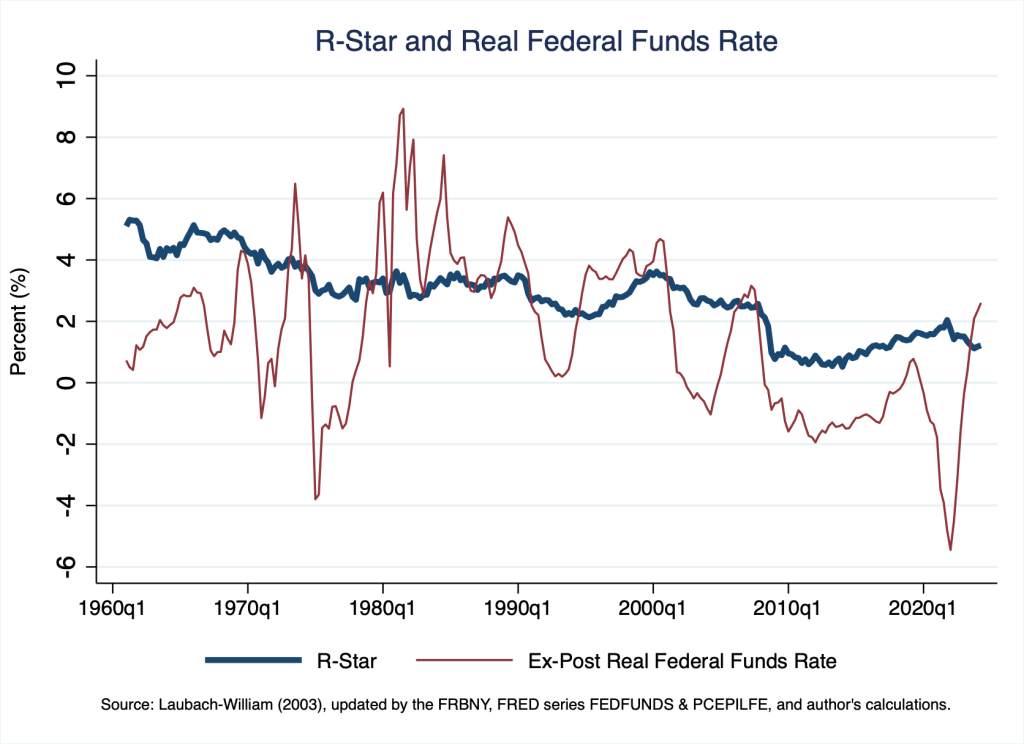

Independent of the policy framework, sensible monetary policy necessarily relies on a counterfactual: the value the operational target—think, the short-term, interbank (federal funds) interest rate—would take if all were right with the macroeconomy. Economists often refer to the counterfactual rate as r-star (). If the central bank wishes to accelerate (decelerate) economic activity, the bank lowers (raises) the federal funds rate below (above)

, for example.

Of course, a counterfactual is, by definition, unobservable. In Figure 2, I illustrate a popular measure of (blue line) and the actual inflation-adjusted (real) federal funds rate (red line) to which we typically compare

.

From the financial crisis in 2008 until very recently, the Federal Reserve targeted the actual real federal funds rate below in an attempt to accelerate economic activity—to stimulate aggregate demand, as it were. Only recently has the actual federal funds rate risen above

—an indication, if we are to believe the counterfactual measure of

I illustrate in Figure 2, monetary policy is currently contracting aggregate demand, all else equal.

Current measures of are generally low by historical standards—think, 1 percent now as opposed to 3 percent in 1980. The central bankers on the panel—namely, Mary Daly and Adriana Kugler—recognized the importance to sensible monetary policy of getting the estimate right, as did John Taylor, who (rightly) includes

in his eponymous rule for monetary policy.

Additionally, the panelists recognized the importance of specifying the so-called Phillips Curve, the relationship—and, in most practical, short-run specifications, the trade-off—between inflation and unemployment. All else equal, whether excess demand or supply conditions in the labor market matter for monetary policy depends on the specification of the Phillips Curve. Reducing the inflation rate is costly in terms of raising the unemployment rate if the Phillips Curve is relatively flat (in unemployment-inflation space), for example.

Throughout the discussion, an underlying theme stood out to me: these days, monetary policy is predicated on the notion that the economy requires active, early, and frequent aggregate demand management by way of a central bank that manipulates an operational target—these days, the federal funds rate. Fiscal policy in the strictest sense—that is, changing tax rates and government spending to achieve macroeconomic goals like full employment and price stability—is practically unavailable. Meanwhile, the tolerance among politicians, policymakers, and, presumably, the public to allow a dynamic, free-enterprise economy to take its course—creating and destroying jobs, firms, and trade patterns, along the way—is quite low. But here is the catch: despite our best intentions, relying on monetary policy to ease the real trade-offs the free market imposes is problematic, if only because evidence monetary policy has long-term impacts on real features of the economy—think, the unemployment rate or the distribution of income—is exceptionally scant.