This blog post accompanies the SDPB Monday Macro segment that airs Monday, April 7. Click here to listen to the segment, which begins at 1 minute into In the Moment.

The U.S. economy is big—like, really big.

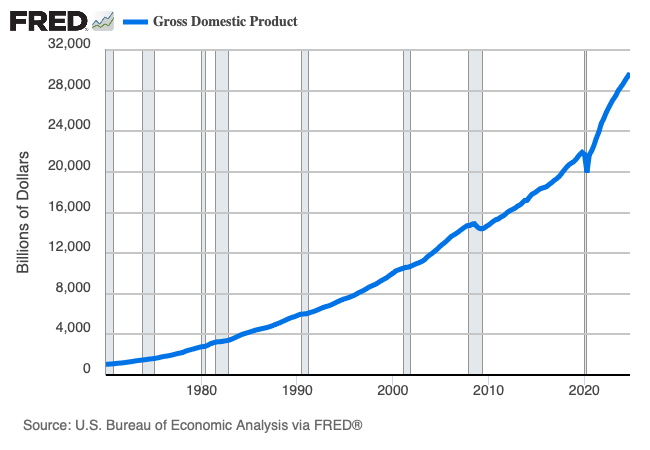

Consider, for example, Figure 1, in which I illustrate nominal GDP, which measures the market value of all final goods and services produced within an economy over an interval of time, typically over a year.

According to Figure 1, as of the fourth quarter of 2024, the U.S. economy, measured by nominal GDP, produced goods and services totaling a market value of $30 trillion—as in $30 million, one million times!

Because the U.S. economy is big, we tend not to talk about its features in terms of levels—the dollar value of personal consumption expenditures, for example. Instead, to gain a more manageable sense of the features of the economy—in addition to personal consumption expenditures, think, the federal debt, exports of goods and services, or defense spending, for example—we tend to scale the features, often by the size of the economy measured as GDP. So, rather than report, say, the level of personal-consumption expenditures in the fourth quarter of 2024 as $20 trillion, we tend to report personal-consumption expenditures as 68 percent of GDP, for example.

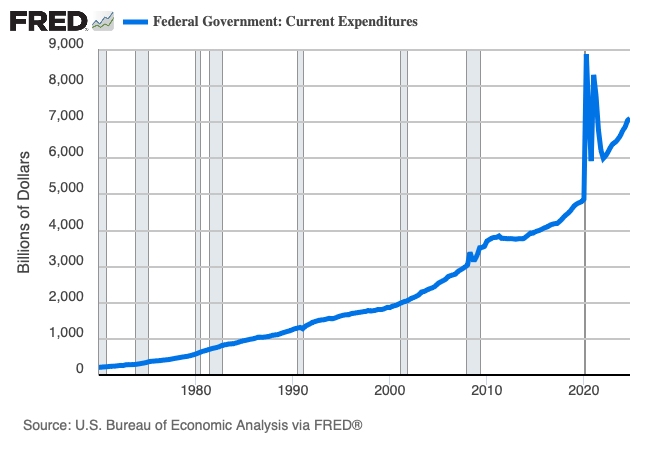

As a rule, scaling macroeconomic variables is sensible; but there are exceptions to the rule, most notably, when our focus is the change in the level of the macroeconomic variable—think, the decrease in the level of federal government expenditures for which we might wish—and thus, the efforts to which we must go to bring about the decrease. Noting that federal government expenditures (Figure 2) in the fourth quarter of 2024 registered 24 percent of GDP distracts us from the fact that the level of federal government expenditures in the fourth quarter of 2024 registered $7 trillion—as in $7 million, one million times.

Decreasing federal government expenditures is understandably front of mind these days, in large part because the federal budget deficit, which we think about as the (negative) difference between government revenues and government expenditures, is big—again, like, really big: for fiscal year 2024, roughly 6 percent of GDP, but what does that mean…in levels?

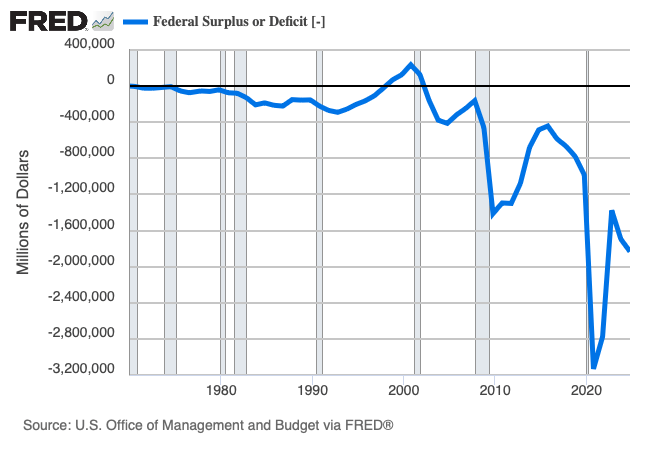

According to Figure 3, in which I illustrate the federal budget deficit in levels, as of the fourth quarter of 2024, a deficit of 6 percent of GDP translated to a deficit of $1.8 trillion.

Recall, a deficit is a flow variable, one we define over an interval of time—think, a fiscal year. Thus, to reduce the deficit permanently, we must reduce federal base, as opposed to one-time, expenditures. And to reduce the deficit meaningfully, we must reduce federal base expenditures materially—that is, by a lot.

The implications for government as we know it are staggering. Consider, for example, the select mandatory, discretionary, net-interest, and other federal budget items I list in Table 1 for fiscal year 2024, when the federal budget totaled $6.8 trillion.

| Mandatory | Budget |

| Social Security | $1.5 trillion |

| Medicare | $865 billion |

| Medicaid | $618 billion |

| Income Security Programs | $370 billion |

| Discretionary | |

| Defense | $850 billion |

| Non Defense | $960 billion |

| Net Interest | $881 billion |

| Other | $752 billion |

Source: Congressional Budget Office

The items I list as mandatory, discretionary defense, and net interest are attached to relatively large budgets. The $6.8 billion federal budget includes many more items attached to relatively small budgets and included in discretionary non-defense and other items; the latter include retirement benefits for federal civilian employees, military personnel, and veterans, for example.

In general, permanently reducing a budget item attached to a budget of any size would permanently reduce the budget deficit accordingly, of course; reducing a budget by, say, $1.7 billion—no small amount of money for you and me—would reduce the deficit by $1.7 billion, as well. But practically speaking, scale matters: reducing budgets by $1.7 billion each to eliminate a budget deficit of $1.7 trillion would require reducing 1,000 budgets by $1.7 billion!

Ok, so what if we go big? For the sake of argument, consider an outrageous thought experiment: suppose we sought to eliminate the budget deficit of $1.7 billion by eliminating wholesale select items I list in Table 1; what might such an approach require? Some rough-estimate options include, for example, eliminating all discretionary spending ($1.8 trillion), including military spending, or eliminating (presumably mandatory) Social Security and income-security-program spending ($1.9 trillion), or eliminating (presumably mandatory) Medicare, Medicaid, and income-security-program spending ($1.8 trillion).

Not a lot of good options, to be sure.

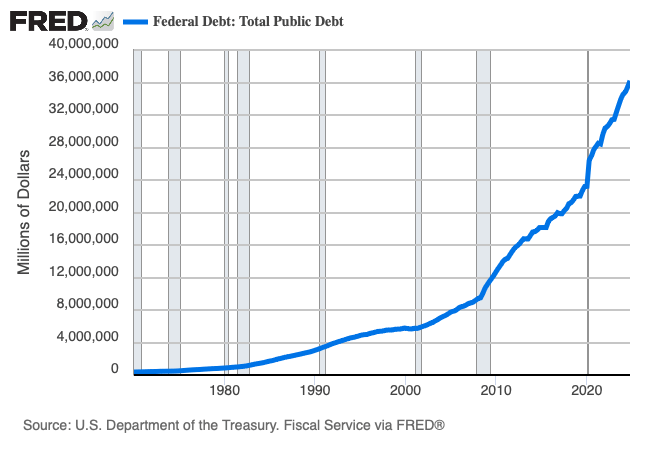

In the meantime, the federal debt, to which annual federal deficits (Figure 3) contribute, continues to grow. Again, economists tend to think about the federal debt in relation to the scale of the U.S. economy: the total federal debt outstanding registers about 120 percent of GDP, for example. But what if we think about the federal debt in levels, which I illustrate in Figure 4?

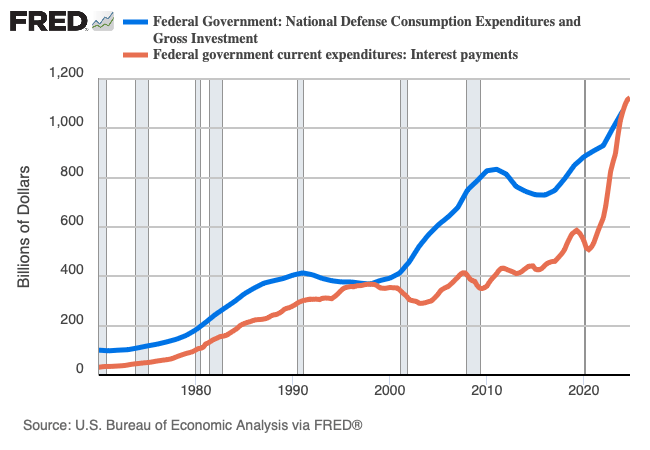

According to Figure 4, as of the fourth quarter of 2024, total federal debt outstanding registered $36 trillion—as in $36 million, one million times. Incidentally, all else equal, the debt grows in part because the U.S. Treasury must pay interest on the debt. According to Table 1, in fiscal year 2024, net interest registered $881 billion, nearly a trillion dollars, about half the level of the federal budget deficit, and more than defense discretionary spending ($850 billion; Figure 5).

Implementing policies to increase or decrease macroeconomic variables—government expenditures, budget balances, public debt outstanding, or otherwise—to improve economic outcomes is sensible, of course. Because few, if any, good options are available to policy makers to improve the budgetary position of the federal government, for example, does not mean policy makers should not try. But to succeed, policy makers must appreciate scale; big changes to you or me are often, in the context of the U.S. economy, rounding errors, as it were—the stuff we rightly eliminate when we eliminate waste, fraud, and abuse, perhaps, but far less than what we must eliminate (or what we must raise in taxes) to improve the budgetary position of the federal government. To effect bigger, long-term meaningful changes in the U.S. economy, we must design macroeconomic policies sensibly and to scale.