This blog post accompanies the SDPB Monday Macro segment that aired on Wednesday, May 21, 2025. Click here to listen to the show, which begins at 23:40.

The debate about trade policy—and specifically, the imposition of across-the-board tariffs for whatever reason—often overlooks the symbiotic relationship between U.S. trade deficits and the U.S. dollar as the dominant world reserve currency. Though I suspect the debate will overlook the relationship no more.

On April 19th, the The Economist displayed on its cover a modified version of Edvard Munch’s The Scream titled, “How a dollar crisis would unfold,” and on May 16th, Moody’s Investors Service, a big-three bond-rating agency, downgraded U.S. sovereign debt—think, dollar-denominated U.S. Treasury bills, notes, and bonds—from the agency’s highest level of Aaa to Aa1. Driving its downgrade, Moody’s cited persistent fiscal deficits, escalating fiscal debt, rising interest payments on the fiscal debt, and political gridlock inhibiting successive presidential administrations and congresses to manage the federal budgetary position. Prior to the Moody’s downgrade, Fitch and S&P downgraded U.S. sovereign debt from AAA to AA+ on August 1, 2023 and August 5, 2011, respectively.

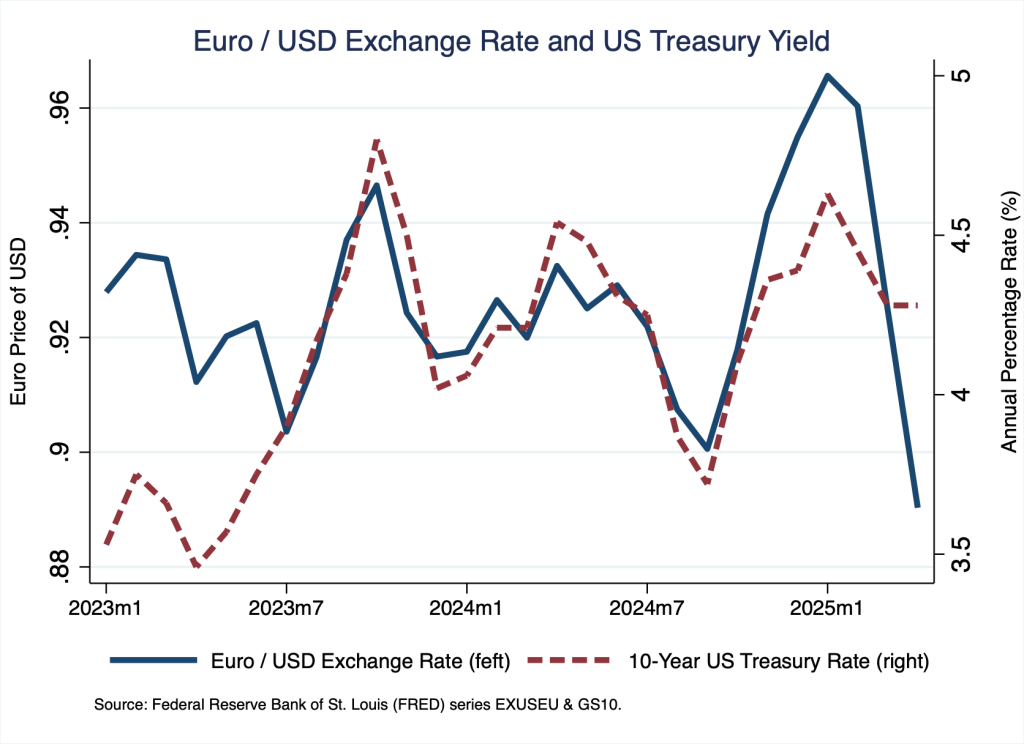

Meanwhile, on balance, the foreign-exchange value of the U.S. dollar has fallen in recent weeks, seeming to violate the otherwise-reliable co-movement of the foreign-exchange value of the U.S. dollar and the yield to maturity on U.S. Treasury bonds implied by the interest-rate parity condition. (For more on the interest-rate parity condition, see Monday Macro post, “Disparity.”) In Figure 1, I illustrate the pattern—the co-movement and its recent violation—in the case of the Euro / USD exchange rate.

The concern about the U.S. dollar is not driven by the trade deficit as such, but rather the (heretofore?) symbiotic relationship between the trade deficit and dollar-denominated debt held by investors, including foreign private investors and foreign governments.

Principally, the trade balance (NX) is an outcome of domestic features of the U.S. economy, which we represent as GDP (Y) in terms of its components of expenditures: namely, consumption expenditures (C), investment expenditures (I), and government expenditures (G), as follows.

Put differently, then, we could think about the trade deficit, in which case NX is negative, as the difference between GDP and consumption, investment, and government expenditures, as follows.

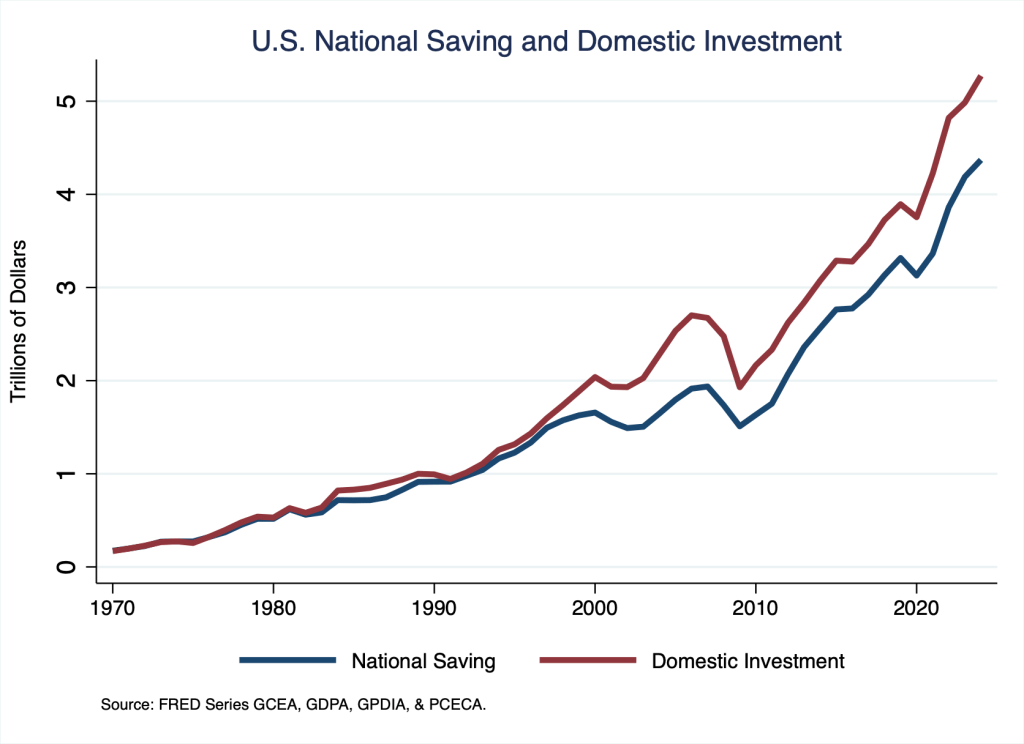

In plain English—and perhaps somewhat ironically—the international trade deficit with the rest of the world (NX) is determined by the difference between national domestic saving (Y – C – G) and domestic investment (I), both of which the domestic features of the U.S. economy determine, by definition. In Figure 2, I illustrate national domestic saving (in blue) and domestic investment (in red); in 2024, for example, the difference between the two measures registered $0.9 trillion, precisely the the size of the U.S. trade deficit in 2024.

Moreover, we could think of national domestic saving as the sum of private saving and public saving, as follows.

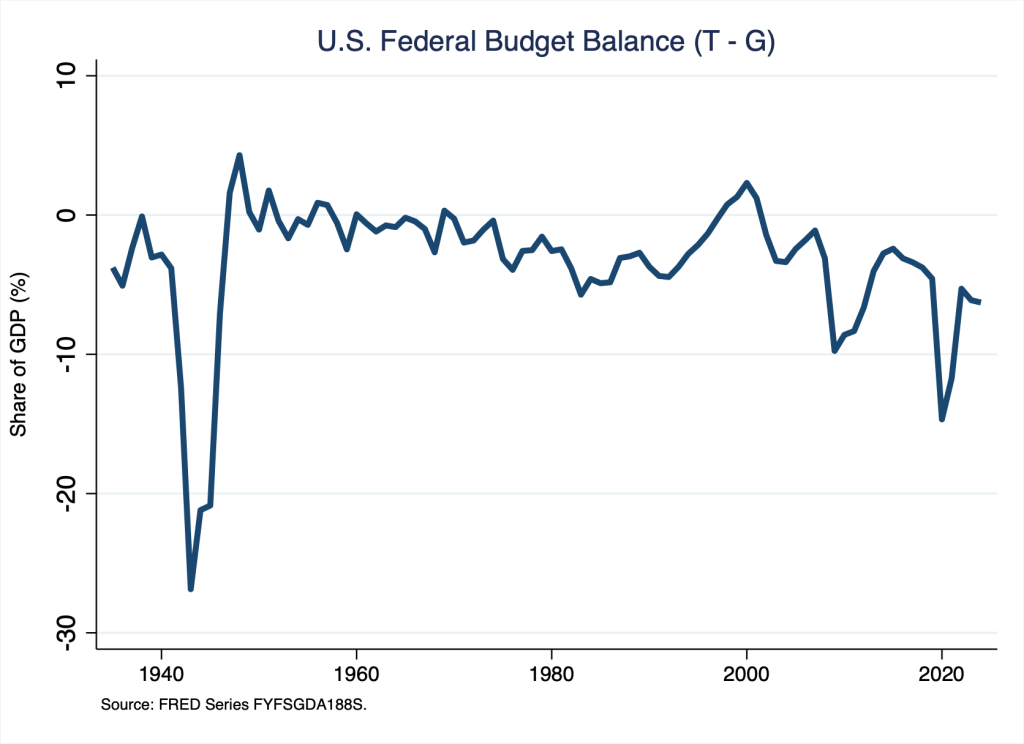

Again in plain English, a trade deficit with the rest of the world is determined by the difference between private domestic saving (Y – C – T), public domestic saving (T – G), and domestic investment (I). For concreteness, think about public saving as the balance of the federal budget; because in reality T – G is negative, public domestic saving registers a federal budget deficit. In practice, then, the U.S. federal budget deficit contributes to the U.S. trade deficit, even though in principal a federal budget deficit is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition of a trade deficit—a subtle, but important point. In Figure 3, I illustrate the U.S. federal budget balance, which registered a deficit of $1.8 trillion (or about 6 percent of GDP) in fiscal year 2024.

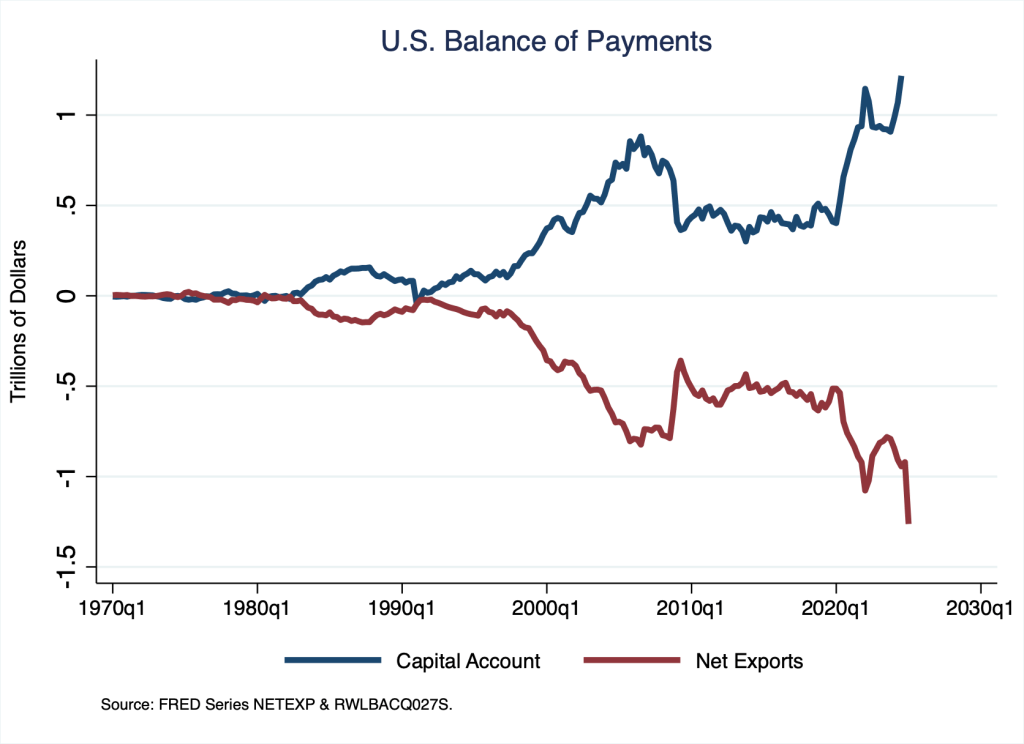

In effect, because the U.S. maintains a trade deficit—for better or worse, no judgement here—foreigners must finance it: if we hold foreign-sourced goods and services on net, foreigners hold U.S. dollars and thus, dollar-denominated financial assets on net. A trade deficit, which belongs to and largely comprises the so-called current account of the balance of payments, must be financed by net lending from foreigners, which belongs to the so-called capital account of the balance of payments. In Figure 4, I illustrate net exports (in red) and the capital account (in blue); the mirror image reflects the necessary foreign net financing of U.S. net exports. [Note, in Figure 2, the data are annual and extend to 2024; in Figure 4, the data are quarterly and extend to the first quarter of 2025.]

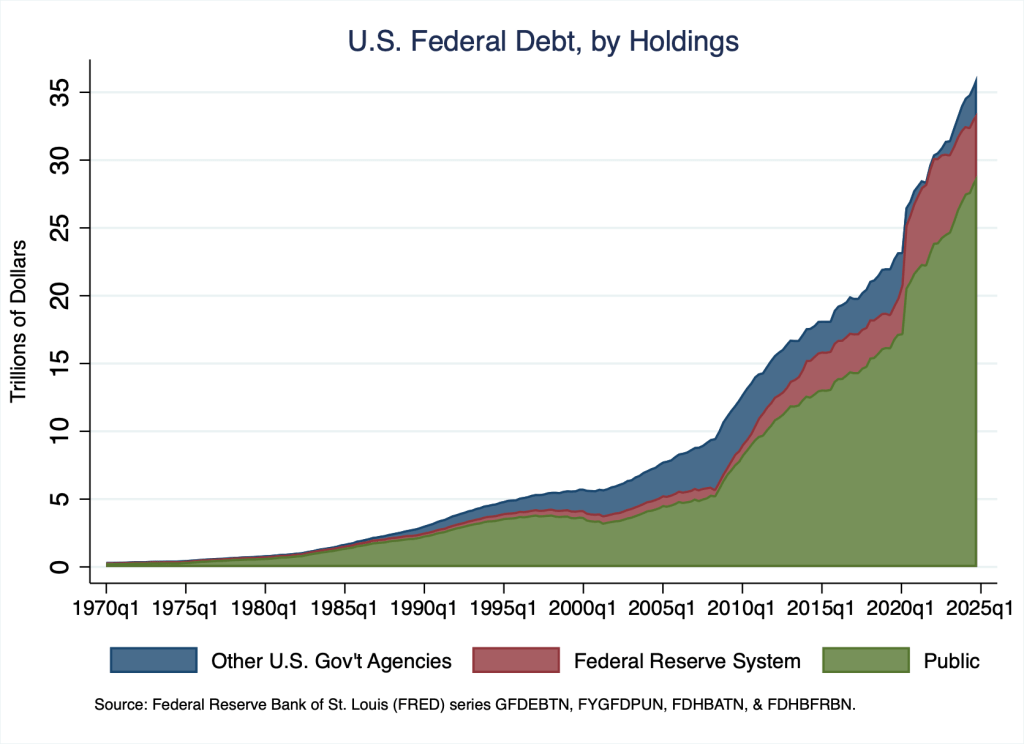

As a practical matter, the dollar-denominated financial assets held by foreigners include trillions of dollars of U.S. Treasury bills, notes, and bonds, because financing persistent and large budget deficits (Figure 3) grows the federal debt (Figure 5), which is comprised of $37 trillion of U.S. Treasury bills, notes, and bonds; and because the U.S. dollar is the dominant world reserve currency, which foreign governments choose to hold as a store of value, largely in the form of U.S. Treasury bills, notes, and bonds.

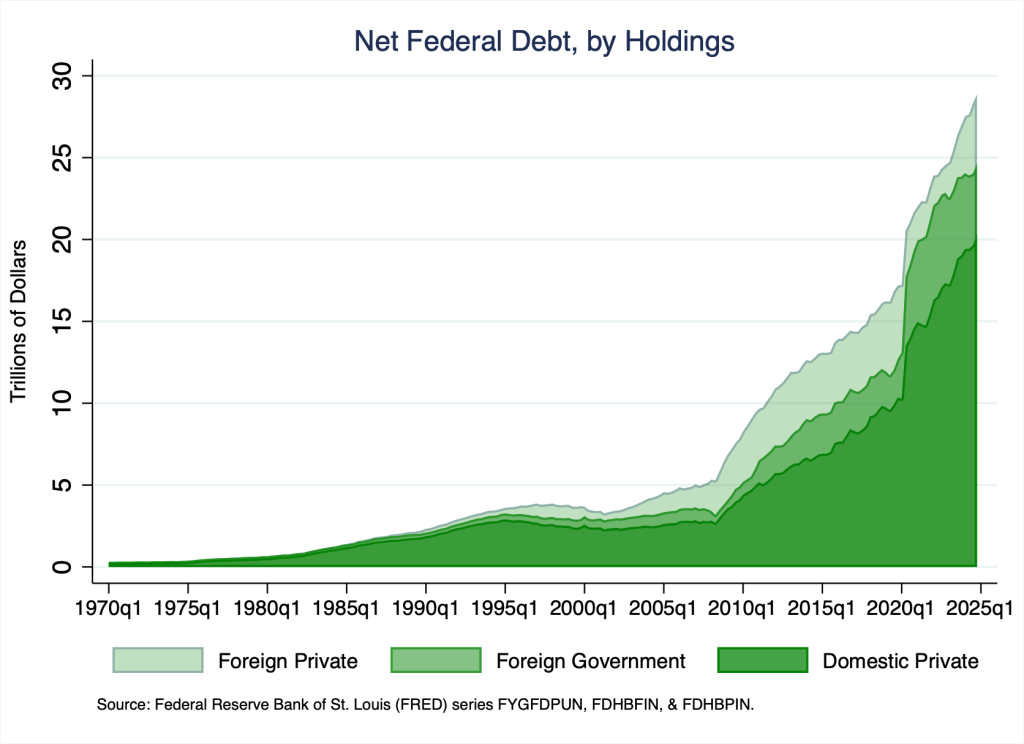

Indeed, of the roughly $28 trillion of federal debt held by the public (Figure 5, green cross section), roughly $8.5 trillion is held by foreign private investors and foreign governments (Figure 6, light and medium-green cross sections).

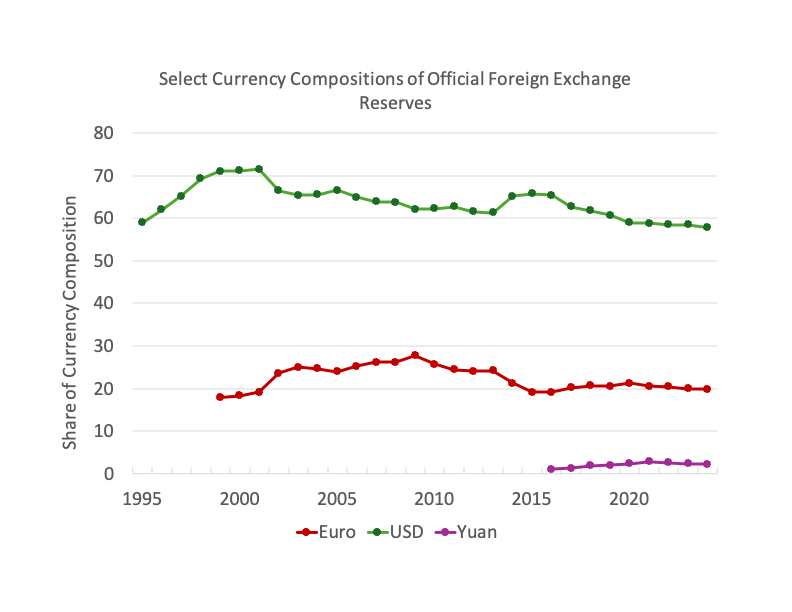

Foreign investors choose to hold U.S. Treasury bills, notes, and bonds because the U.S. dollar is the dominant world reserve currency and because the U.S. Treasury security is the dominant default-risk free, liquid world reserve debt instrument. To illustrate the dominance of the U.S. dollar, in Figure 7, I illustrate the composition of official foreign exchange reserves—think, other countries’ currencies held by central banks as reserve assets—in terms of dollars, euros, and yuan; the illustration is not exhaustive: other currencies not illustrated in Figure 7 comprise (relatively small shares of) foreign exchange reserves, as well.

According to Figure 7, the U.S. dollar comprises the largest share of foreign exchange reserves, though the share has fallen from its local high registered a few years after the global financial crisis.

The U.S. trade and federal budget deficits are symbiotically related to the U.S. dollar as the dominant world reserve currency, an exorbitant privilege the world financial system affords the United States because of its social infrastructure—rule of law, independent judiciary, prudential budgetary practices, and reliably rational and predicable policy making, for example. The current debates about trade and budgetary policies are effectively debates about the resilience of U.S. social infrastructure. All else equal, tariffs are blunt and ineffective policy instruments—this we know. We do not know if U.S. policies—trade, budgetary, or otherwise—and how the U.S. government implements the policies are consistent with preserving U.S. social infrastructure and thus, U.S. dollar dominance, the known unknown driving concerns about the U.S. dollar.

And I know, I know: there is no alternative to the U.S. dollar and the one-of-a-kind liquid and deep U.S. Treasury market—an explanation we have heard many times. Unfortunately, as in politics, so too in international finance: when you’re explaining, you’re losing.