This blog post accompanies the SDPB Monday Macro segment that airs on Tuesday, April 2, 2024. Click here to listen to the show. For more macroeconomic analysis, follow J. M. Santos on Twitter @NSMEdirector.

In 1895 in response to rumors he was dead, Samuel Clemens—aka, Mark Twain—quipped, “The report of my death was an exaggeration.” And so it goes with commercial real estate, an industry sector observers seem quick to declare dead or dying, the supposed trigger of banking panics, financial crises, and macroeconomic contractions. For example, a quick search, via Economist.com, of the Economist magazine based on keywords, “commercial real estate,” published since the pandemic yielded the following foreboding headlines.

Is investors’ love affair with commercial property ending?

— June 25, 2020What a work-from-home revolution means for commercial property

— June 3, 2021Recession fears weigh on commercial property

— July 26, 2022Commercial-property losses will add to banks’ woes

— March 29, 2023Is working from home about to spark a financial crisis?

Source: Economist.com search results for “commercial real estate.”

— February 14, 2024

The latest reports of the death of commercial real estate result from two forces: one epidemiological and one macroeconomic. The epidemiological force is, of course, the pandemic, which instigated a work-from-home movement, reducing demand for office space and shifting demand for retail services—less demand for bricks and mortar retail downtown in some cases, more demand for online retail in all cases, for example. The macroeconomic force is tight Federal Reserve monetary policy, which the central bank initiated in 2022 to reduce the growth of aggregate demand and, thus, the rate of inflation.

Operationally, to tighten monetary policy, the Federal Reserve raises the federal funds rate, the (interbank) rate banks charge each other for bank reserves—inventories, essentially, that banks manage in order to generate earnings (by lending reserves to borrowers) and to maintain liquidity (by storing reserves for cash-seeking depositors). The Federal Reserve rather precisely targets the federal funds rate; the rate typically moves within a narrow target range of 25 basis points. The central bank’s dual (Congressional) mandate of maximum employment (and, thus, output at or very near its potential) and stable prices (and, thus, low and stable inflation) informs where the central bank sets this operational target of monetary policy.

At any moment, the federal funds rate reflects the so-called stance of monetary policy: expansionary—and a relatively low federal funds rate—if output is below potential or inflation is below the two-percent target rate; or contractionary—and a relatively high federal funds rate—if output is above potential or inflation is above the two-percent rate. Currently, the stance is contractionary—think, tight monetary policy—because inflation remains elevated, though much less so than during 2022 and 2023. Over the last 24 months, the central bank has raised the federal funds rate from 0 to 0.25 percent to 5.25 to 5.50 percent.

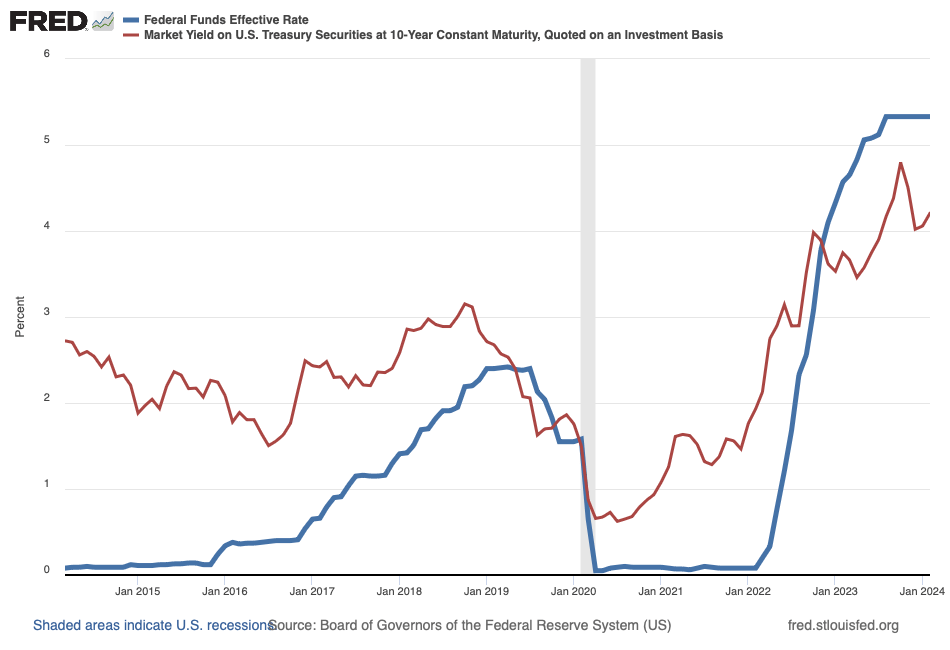

In Figure 1, I illustrate the federal funds rate (blue line) alongside the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond yield to maturity (red line)—the interest rate the federal government pays to borrow money for a decade.

To be sure, the monetary tightening has been aggressive; so much so that the central bank has now raised the (short-term) federal funds rate above the (long-term) U.S. Treasury bond rate. Typically, we expect the long-term rate to rise along with, but not be outpaced by, the short-term rate, because we expect the long-term rate—think, the 10-year yield I illustrate in Figure 1—to be determined largely by the average of current and expected-future short-term rates—think, the path of current and expected federal funds rates of the sort I illustrate in Figure 1. (For more on the yield curve, and how long-term and short-term yields are theoretically related, see the Monday Macro segment, Yield to (Fiscal) Maturity.) In any case, higher interest rates matter a great deal to commercial real-estate markets, thanks to the time value of money.

Ignore the time value of money at your peril.

Commercial property values are inversely related to interest rates—and, thus, monetary tightening—because today’s value of a dollar received now is greater than today’s value of a dollar received later: because the interest rate, the so-called opportunity cost of holding money, is positive, to generate one dollar one year from now—the future value—we need less than one dollar today—the present value. For example, to generate one dollar one year from now at an interest rate of 5 percent, we need $0.95 today.

To understand this concept of the time value of money in the context of commercial real estate, think of the present value of a commercial property as , the price of the property at time zero—that is, now. If property markets are efficient, and thus no one leaves money on the table as it were,

must equal the present value of the stream of annual returns—think,

—the property would generate. Put differently,

must equal the amount of money I must invest today at the prevailing interest rate to generate—think, to match—the stream of payments the property would otherwise generate. The higher the prevailing interest rate, the less the amount of money I must invest today—the less

must be—to match the stream of payments the property would otherwise generate.

More precisely, the present value of, say, is

, where

is the interest rate; analogously, the present value of, say,

is

; and so on. Thus, the present value of an asset—commercial property or otherwise—is inversely related to the interest rate because the higher the interest rate, the less a payment arriving in the future is worth today.

Finally, in the case of annual returns—think again,

—and a sale of the property in period

that generates

, in an efficient commercial property market,

satisfies the following present-value equation.

The key takeaway from the equation is that equals an expression (on the right side of the equals sign) in which each payment is divided—or, in the parlance of finance, discounted—by the interest rate,

; for each future payment, the larger the interest rate, the larger the denominator, the larger the discount, the smaller the present value.

The macroeconomic force is making matters worse for commercial real estate.

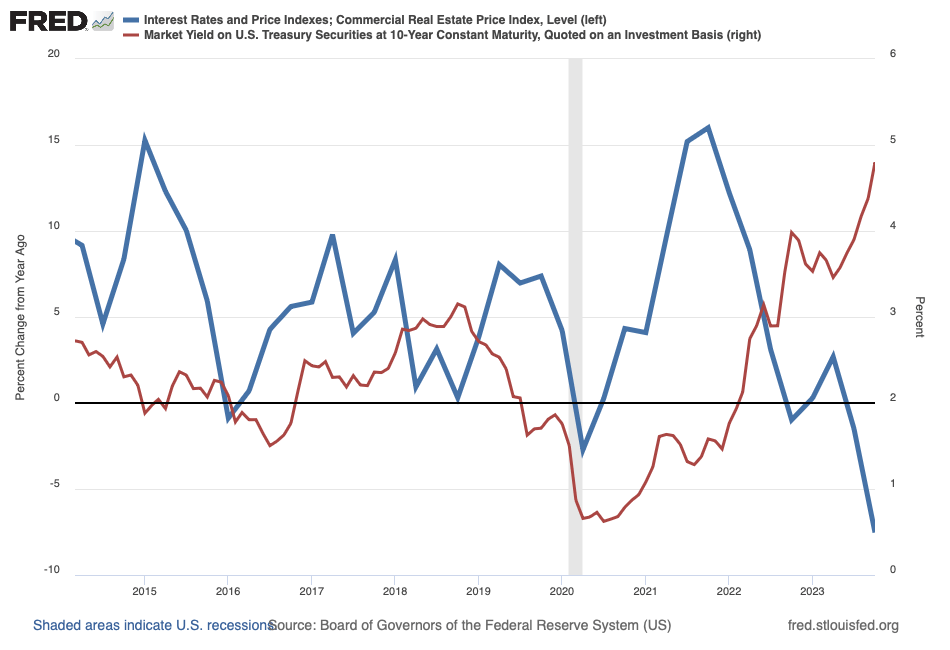

In Figure 2, I illustrate the year-over-year percentage change in a commercial real-estate price index—values below zero indicate a year-over-year fall in the average price of commercial real estate—alongside the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond yield to maturity I illustrate in Figure 1.

According to Figure 2, the post-covid, persistent fall in the average price of commercial real estate (blue line; left scale) that began around the start of 2022 coincided with the rise in interest rates (red line; right scale) instigated by monetary tightening. Indeed, the inverse relationship between commercial property values and interest rates is clearly evident post covid; note the “X” shape traced out by the blue and red lines beginning around mid 2021: all else equal, commercial property values fall [rise] as interest rates rise [fall], as the theory of the time value of money and, specifically, its present-value equation imply.

During monetary tightening, bank on commercial real-estate troubles.

Price pressures in commercial real-estate markets—think, the blue line I illustrate in Figure 2—reflect broader, though less-than-catastrophic, troubles, which we could observe indirectly on the balance sheets of the nation’s commercial banks, the intermediaries that finance a significant portion of commercial real-estate development.

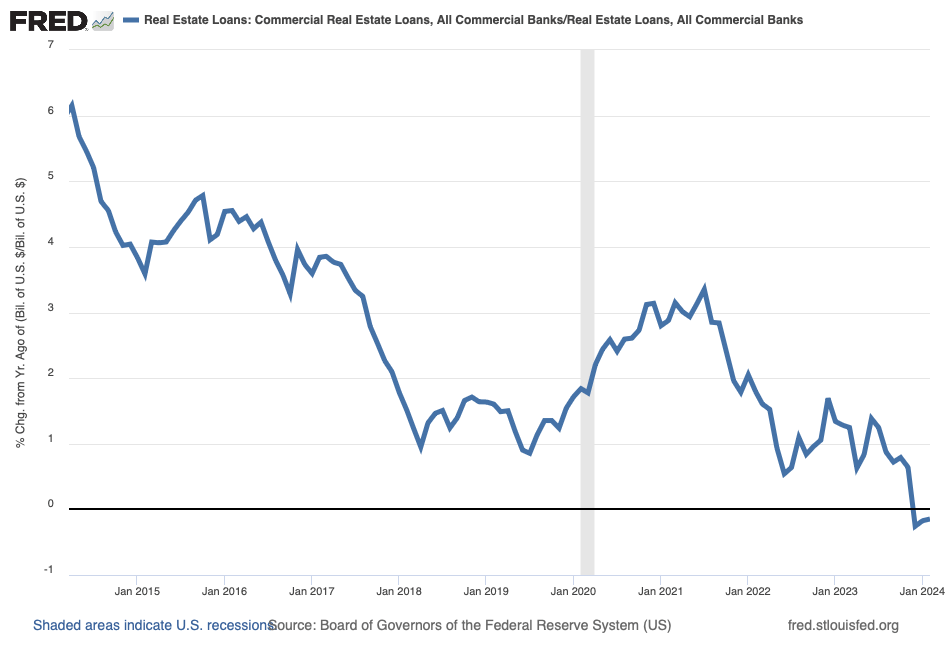

In Figure 3, I illustrate for all commercial banks in the United States, the year-over-year percentage change in the share of the total dollar value of real-estate loans comprised of commercial-real estate loans (as opposed to residential or industrial real-estate loans, for example).

According to Figure 3, recently banks have proportionally reduced the dollar value of commercial real-estate loans, a pattern visible in the figure where the blue line drops below zero (for the first time in a decade). Importantly, Figure 3 does not imply the dollar value of commercial real-estate loans has fallen—it has not; rather, the figure implies the dollar value of commercial real-estate loans has fallen as a share of the total dollar value of all real-estate loans. Put differently, the fall I illustrate in the figure is subtle, though unlike anything we have observed in the last ten years.

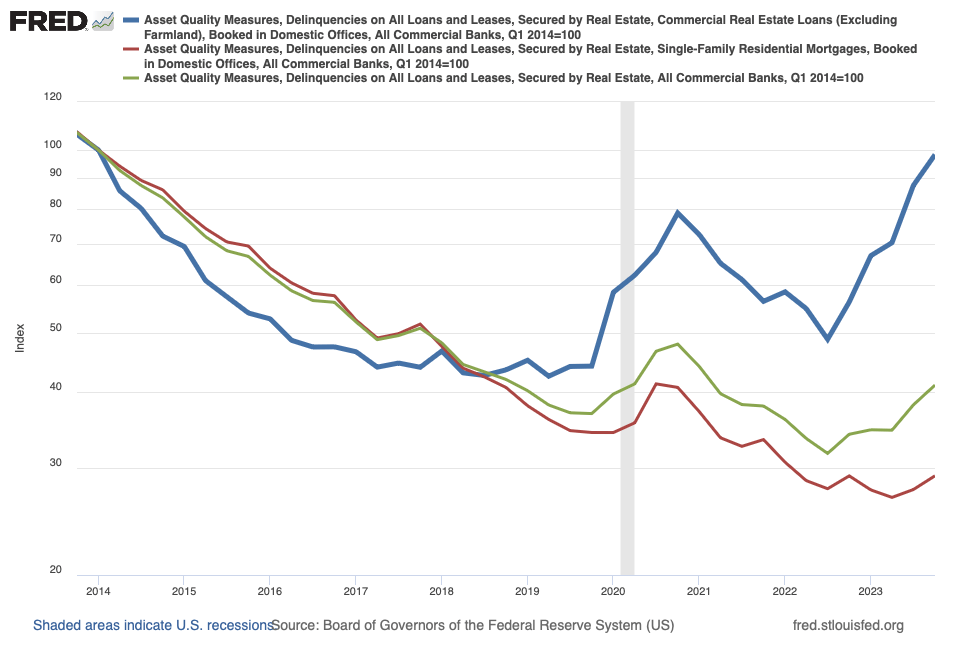

Perhaps of greater concern is the rise in delinquencies—the dollar value of loans and leases past due thirty days or more—on bank loans secured by commercial real estate. In Figure 4, I illustrate, as an index on a log scale, delinquencies for the dollar value of bank loans secured by commercial real estate (blue line), of bank loans secured by single-family residential real estate (red line), and of bank loans secured by all real estate combined (green line); the log scale allows us to compare vertical distances traveled by lines in the figure as proportional changes, because the growth rate attached to a given vertical distance traveled by a line in the figure is unaffected by the starting value of the distance traveled: large [small] vertical distances imply large [small] growth rates.

According to Figure 4, since 2022, when the Federal Reserve began to tighten monetary policy, the proportional rise in delinquencies on the dollar value of bank loans secured by (relatively interest-rate-sensitive) commercial real estate has exceeded the proportional rise in the dollar value of bank loans secured by (relatively interest-rate-insensitive) single-family residential real estate. In the case of commercial real-estate loan delinquencies, the dollar values behind the index I illustrate in Figure 4 are as follows: in the third quarter of 2022, $16 billion of loans were delinquent, whereas in the fourth quarter of 2023, $32 billion of loans were delinquent, an increase of roughly 100 percent. The comparable dollar values for single-family residential real-estate loan delinquencies are $44 billion (2022 Q3) and $46 billion (2023 Q4), an increase of roughly 5 percent.

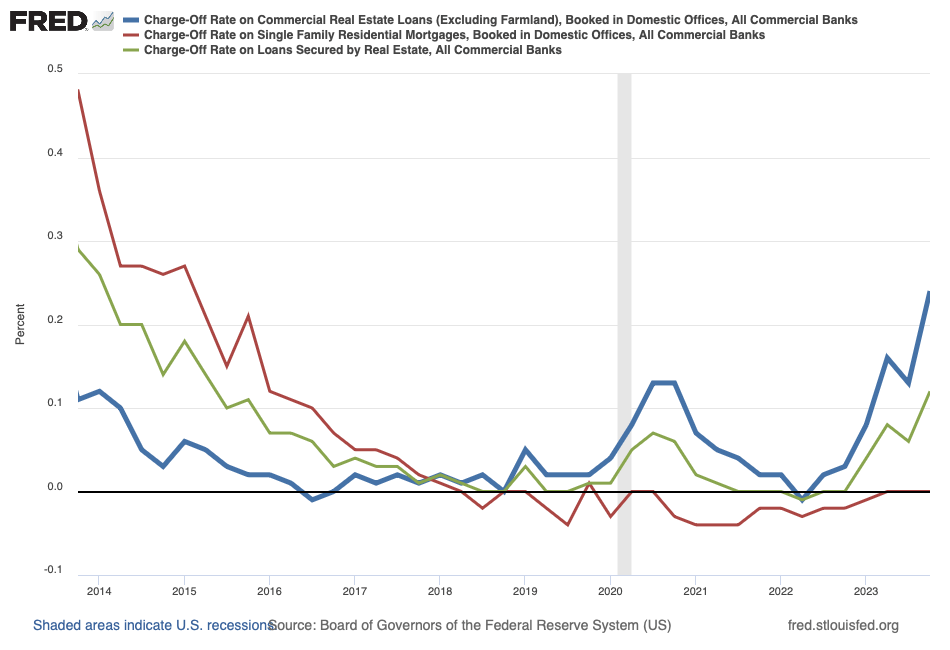

Meanwhile, charge-offs—the dollar value of loans and leases removed from banks’ balance sheets and charged against banks’ loss reserves—have risen as well. In Figure 5, I illustrate, as a percentage of the dollar value of loans secured by a given category, charge-off rates of bank loans secured by commercial real estate (blue line), of bank loans secured by single-family residential real estate (red line), and of bank loans secured by all real estate combined (green line).

According to Figure 5, since 2022, the rise in the charge-off rate of bank loans secured by commercial real estate has exceeded the (non-existent) rise in the charge-off rate of bank loans secured by single-family residential real estate. I reason the relative interest-rate sensitivity of commercial real-estate markets, driven at a macroeconomic level by the time value of money, explains, as it did in the case of delinquencies, the divergent outcomes for charge-off rates in the two real-estate sectors.

Thus, considering how commercial real-estate prices and loans have performed since the Federal Reserve began its latest tightening cycle, higher interest rates have left their mark on the real-estate sector in much the way the theory of the time value of money implies. The troubles in the sector are real and, given the relatively short duration of commercial real-estate loans (which must be refinanced sooner rather than later and, thus, at relatively high current rates), the troubles are likely to continue past the point when the Federal Reserve loosens monetary policy.

Nevertheless, neither the sector nor the broader economy is doomed. This is to say, the answer to the question the Economist magazine posed in February 2024 (“Is working from home about to spark a financial crisis?“) is most likely, “No.” Currently, the troubles in commercial real-estate markets appear idiosyncratic to specific lenders and developers, for example. And in any case, the dollar value of commercial real-estate markets combined amount to a relatively small share of bank lending or gross domestic product. Unlike residential real-estate markets, the scale of commercial real-estate markets and the segment’s multiplier effect on consumption are not large enough to spur independently a macroeconomic crisis.

Finally, like politics, all real-estate markets are local, or at the very least the markets reflect local forces of supply and demand that may exacerbate or ameliorate the effect of the macroeconomic force of a tight monetary policy. To learn more about how commercial real-estate markets currently fare in South Dakota, home to Schooled, Monday Macro, and the Ness School of Management and Economics at South Dakota State University, I defer to a local expert: on the SDPB Monday Macro segment that airs on Tuesday, April 2, 2024, Michael Bender, founder and principal of Bender Commercial based in Sioux Falls, SD, joins Lori Walsh and me in the SDPB studio to discuss the outlook for commercial real-estate markets in the region. Don’t miss it!