This blog post accompanies the SDPB Monday Macro segment that airs on Monday, August 5, 2024. Click here to listen to the show, which begins at minute 16:00.

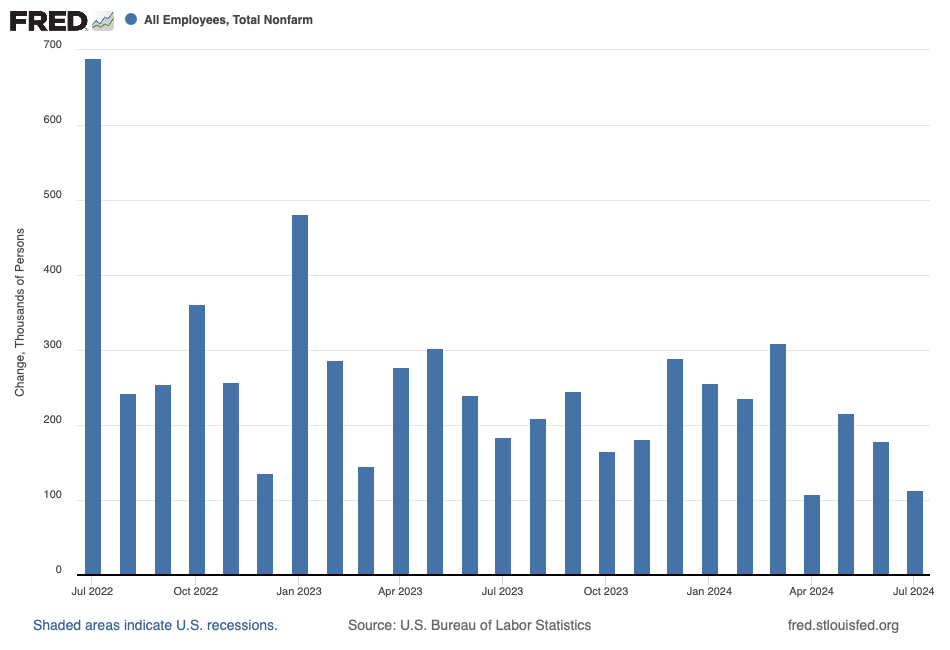

On Friday, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported the U.S. economy added 114,000 jobs (on net) in July. In Figure 1, I illustrate the number of jobs created in the U.S. economy each month since July 2022; to be sure, compared to the number of jobs created over the last few years, the number registered in July was relatively—though not exceptionally—low. On balance, macroeconomists expected the economy to create about 175,000 in July.

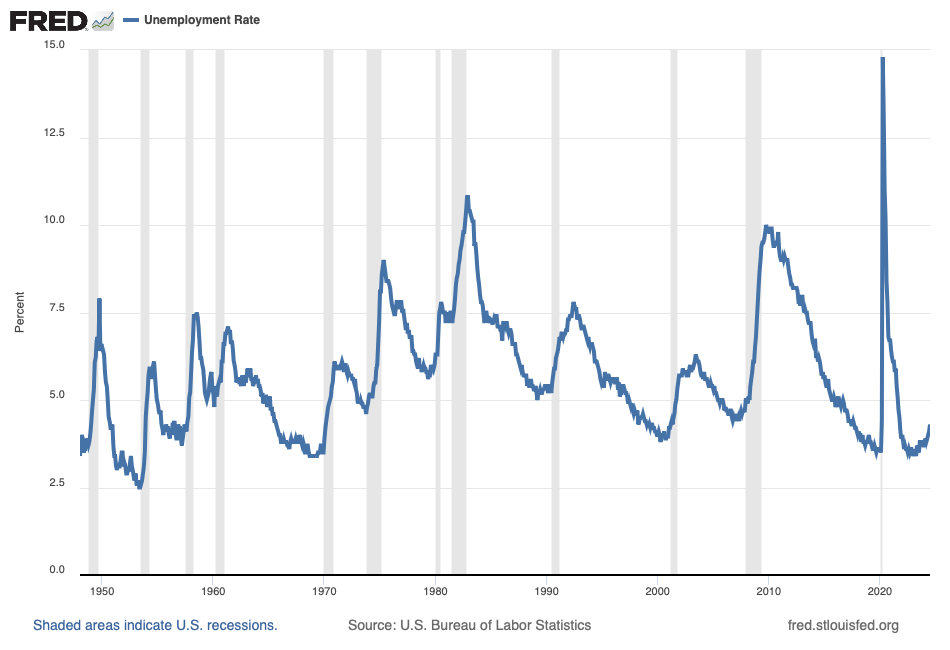

Meanwhile, the BLS reported the unemployment rate, which I illustrate in Figure 2, rose to 4.3 percent, its highest level since October 2021, when the U.S. economy was recovering from the pandemic.

In Figure 2, I illustrate the standard, relatively narrow (U3) measure of the unemployment rate often cited in media coverage of the labor market. To calculate the measure, the BLS divides the number of unemployed individuals by the number of individuals in the labor force—the number of unemployed individuals plus the number of employed individuals. As Monday Macro listeners know well, the unemployment rate is an inherently macroeconomic statistic; it describes a general feature of the economy-wide labor market as opposed to a specific feature of the labor market for, say, automobile mechanics in Kentucky or dentists in South Dakota.

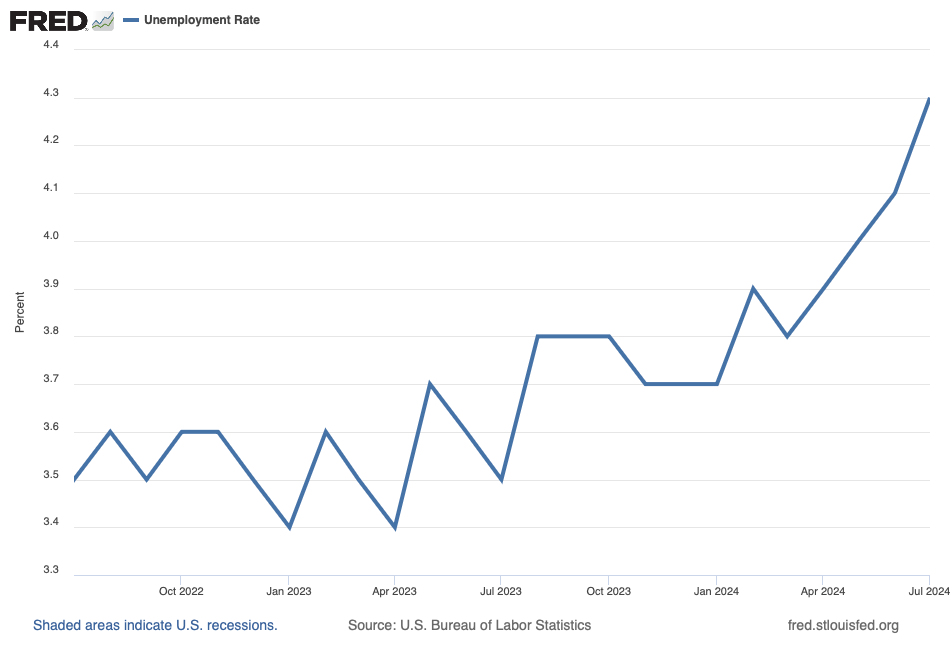

To gain a better visual sense of how the unemployment rate illustrated in Figure 2 has risen recently, in Figure 3, I illustrate the rate since January 2022, after the pandemic-induced spike in the rate completely reversed course.

According to Figure 3, the unemployment rate rose from 3.8 percent in March 2024 to 4.3 percent in July 2024, a fifty-basis-point increase in the rate in four months. Understandably, many macroeconomists have grown alarmed by the recent pattern of deterioration in the labor market.

That special Sahm thing

One macroeconomist, Claudia Sahm, the director of macroeconomic policy at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth and formerly with the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, has grown particularly alarmed.

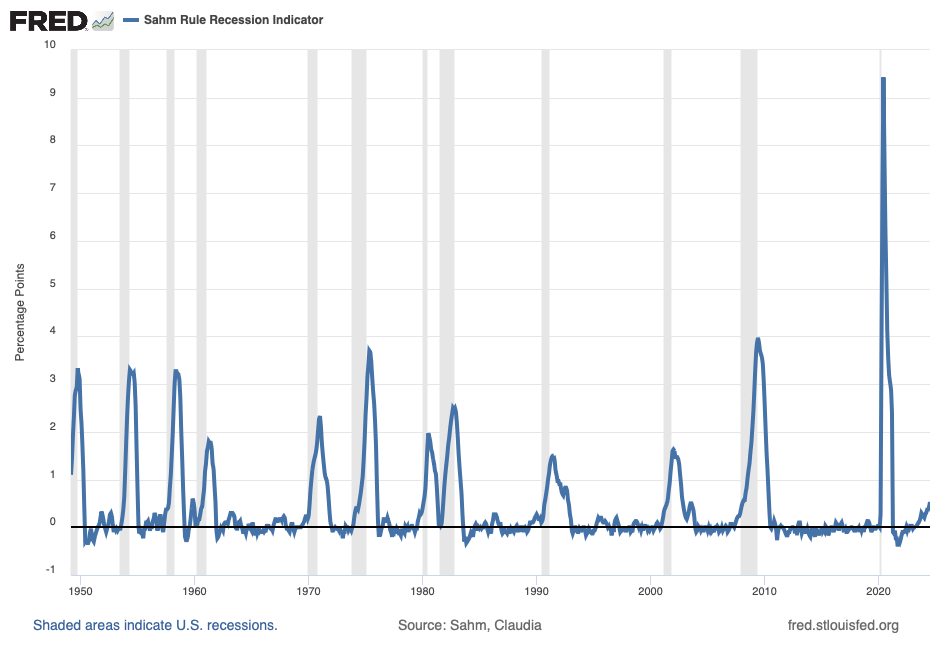

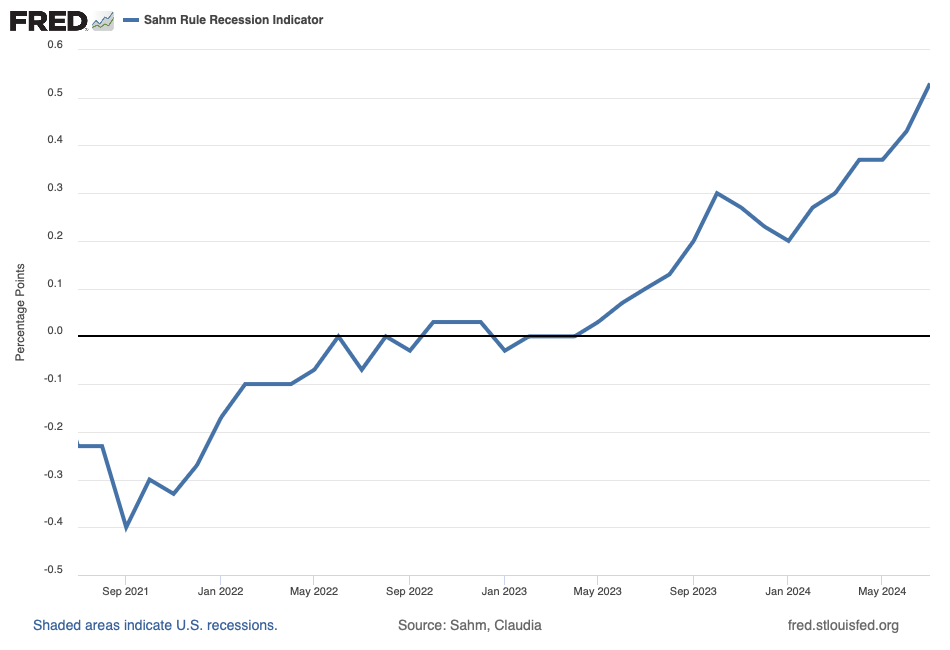

Claudia Sahm created the eponymous Sahm-rule indicator (of recessions). According to Sahm, the rule signals a macroeconomic recession when the three-month moving-average unemployment rises by at least a half of a percentage point above the lowest three-month moving-average unemployment rate in the previous 12 months. In Figure 4, I illustrate the Sahm-rule indicator, complete with gray recession bars based on business-cycle peak and trough dates supplied by the Business-Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

According to Figure 4, each time the Sahm-rule indicator exceeded the half of one percentage point threshold, a business-cycle recession (indicated by a gray, vertical bar) soon followed. Moreover, throughout the Post-WWII era illustrated in Figure 4, the Sahm rule essentially never produced a false positive: this is to say, the rule never registered a value above 0.5 without a recession following immediately or very soon thereafter. In Figure 4, the most recent data point corresponds to a Sahm-rule indicator of 0.53 for July, 2024. In Figure 5, I illustrate the Sahm-rule indicator beginning July 2021, thereby emphasizing the recent rise in the indicator above 0.5.

The unemployment rate rises and falls in response to myriad macroeconomic forces, of course. Given the ongoing efforts of the Federal Reserve to reduce the rate of inflation, and given the short-run trade-off between reducing the rate of inflation and reducing the unemployment rate, it is rising now because of tight Federal Reserve monetary policy. In the parlance of macroeconomics, the central bank seeks to destroy (aggregate) demand—and, if ncessary, employment—to reduce inflation.

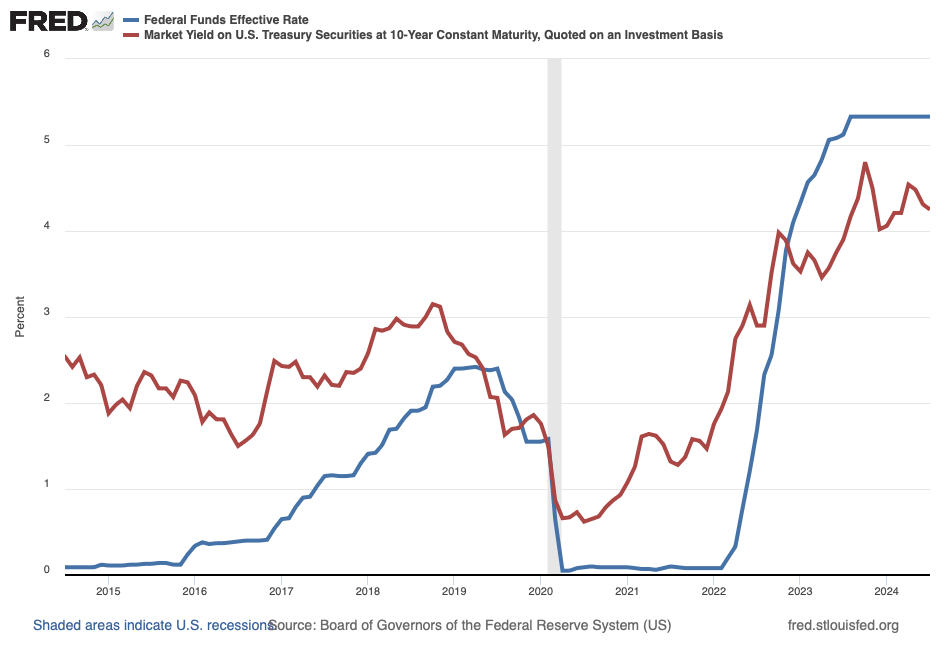

Operationally, to tighten monetary policy, the Federal Reserve raises the federal funds rate, which I illustrate (in blue) in Figure 6.

The federal funds rate is the (interbank) rate banks charge each other for bank reserves—inventories, essentially, that banks manage in order to generate earnings (by lending reserves to borrowers) and to maintain liquidity (by storing reserves for cash-seeking depositors). The Federal Reserve rather precisely targets the federal funds rate; the rate typically moves within a narrow target range of 25 basis points. The central bank’s dual (Congressional) mandate of maximum employment (and, thus, employment at or very near its potential level) and stable prices (and, thus, low and stable inflation) informs where the central bank sets this operational target of monetary policy.

At any moment, the federal funds rate reflects the so-called stance of monetary policy: expansionary—and a relatively low federal funds rate—if output is below potential or inflation is below the two-percent target rate; or contractionary—and a relatively high federal funds rate—if output is above potential or inflation is above the two-percent rate. Currently, the stance is presumably contractionary—think, tight monetary policy—because inflation remains elevated, though much less so than during 2022 and 2023. Over the last 24 months, the central bank has raised the federal funds rate from 0 to 0.25 percent to 5.25 to 5.50 percent.

Claudia Sahm and many other macroeconomists argue the stance of monetary policy has been too contractionary for too long. To be sure, the monetary tightening has been aggressive; so much so that the central bank has now raised the (short-term) federal funds rate above the (long-term) U.S. Treasury bond rate. Typically, we expect the long-term rate to rise along with, but not be outpaced by, the short-term rate, because we expect the long-term rate—think, the 10-year yield I illustrate in Figure 6—to be determined largely by the average of current and expected-future short-term rates—think, the path of current and expected federal funds rates of the sort I illustrate in Figure 6.

Sahm thing or other

Nevertheless, there is reason to wonder if the Sahm rule indicator is signaling (its first) false positive: registering a value above 0.5 without a recession following immediately or very soon thereafter. The reason is based on how the BLS, and economists more generally, define the labor force (L): the sum of employed (E) and unemployed (U) individuals——and what this definition implies about movements in the unemployment rate.

According to the BLS, an employed individual is a paid employee or an unpaid employee in a family business. The BLS counts as employed any individual who, at the time the BLS administers its household (employment) survey, is not working because she is on vacation, she is unable to get to work due to inclement weather, or she is ill. Moreover, the BLS counts as employed any part-time employee, whether or not she wishes to be employed full time. In contrast, an unemployed individual is anyone who, during the four weeks preceding the survey, was actively seeking employment or waiting to return to work due to a layoff.

Based on the definition of the labor force, the unemployment rate is, arithmetically speaking, the number of unemployed individuals divided by the labor force, as follows.

For example, suppose the labor force includes 150 million individuals, of whom 7.5 million are unemployed. In this example, the unemployment rate is 5 percent, or 7.5 million divided by 150 million.

Of course, millions of individuals do not belong to either of these categories. This is to say, millions of individuals are neither employed nor unemployed; rather, they are out of the labor force—full-time students or retirees are the simplest examples. In any case, as individuals enter (or re-enter) the labor force as unemployed, the unemployment rate must rise. To the extent individuals enter the labor force because they are attracted to economic opportunities that did not exist before, the concomitant rise in the unemployment rate reflects a good outcome.

In the aftermath of the pandemic and the exceptional fiscal and monetary stimuli households received, there is good reason to suspect individuals who exited the labor force then might be re-entering it now. Indeed, Wells Fargo Economics estimates that in July, entrants—new and re-entrants—to the labor force comprised 22 basis points of the rise in the Sahm Rule indicator over the past year, more than entrants comprised of the rise in the indicator in the first month of each of the past seven recessions (with the exception of 2020). Put differently, had entrants not comprised an outsized portion of the rise in the indicator, it would not signal recession now. As Sarah House and Michael Pugliese of Well Fargo Economics remark in their analysis of the July employment report:

This increase in unemployment [because of re-entrants] for the “right” reasons suggests that the crossing of the 0.5 point threshold may not be the sure-fire sign of recession that it has been in the past.

Nevertheless, House and Pugliese rightly warn conditions in the labor market have deteriorated in any case; unemployment due to permanent job loss or the scheduled end of temporary work has also risen significantly over the past year, including in July, for example.

The question is what the Federal Reserve, which, by tightening monetary policy, has caused conditions in the labor market to deteriorate, should do now. After the employment report on Friday, and its effect on the Sahm-rule indicator, the consensus in the bond market seems to favor accelerated loosening: a 50 basis point reduction in the federal funds rate target sooner rather than later, followed by another reduction by at least as much shortly thereafter, for example.

I would caution against aggressive loosening, absent additional evidence of a weakened labor market—a higher unemployment rate independent of an outsized number of labor-force re-entrants, for example—and weakened inflationary pressures. Based on the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of inflation—the personal consumption expenditures index excluding food and energy—year-over-year inflation remains above 3 percent and the output gap remains positive at about 1 percent of potential real GDP, while measures of the natural rate of interest—so-called —do not precisely indicate the current stance of monetary policy is exceptionally tight.

Excessive tightening destroys jobs, while premature loosening destroys central-bank credibility, a trade-off proponents of accelerated loosening either disregard or appreciate less than I do.

One thought on “sahm thing of a first”