This blog post accompanies the SDPB Monday Macro segment that airs on Monday, February 5, 2024. Click here to listen to the segment, which begins at minute 12. For more macroeconomic analysis, follow J. M. Santos on Twitter @NSMEdirector.

Last week was busy for macroeconomists, particularly those who listened very carefully.

On Wednesday, everyone heard the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the Federal Reserve System concluded its meeting, announcing the central bank would maintain a federal funds rate target range of 5.25 to 5.50 percent, the highest target range in almost a quarter of a century. In Figure 1, I illustrate the federal funds rate.

The federal funds rate is the (interbank) rate banks charge each other for bank reserves—inventories, essentially, that banks manage in order to generate earnings (by lending reserves to borrowers) and to maintain liquidity (by storing reserves for cash-seeking depositors). The Federal Reserve rather precisely targets the federal funds rate; the precision explains the step-function pattern of the federal funds rate I illustrate in Figure 1: the rate generally moves within a narrow target range (of 25 basis points currently), making the time series appear as steps. The central bank’s dual (Congressional) mandate of maximum employment (and, thus, output at or very near its potential) and stable prices (and, thus, low and stable inflation) informs where the central bank sets this operational target of monetary policy. (For more on the dual mandate, see the Morning Macro segment, “Mind the Gaps.”)

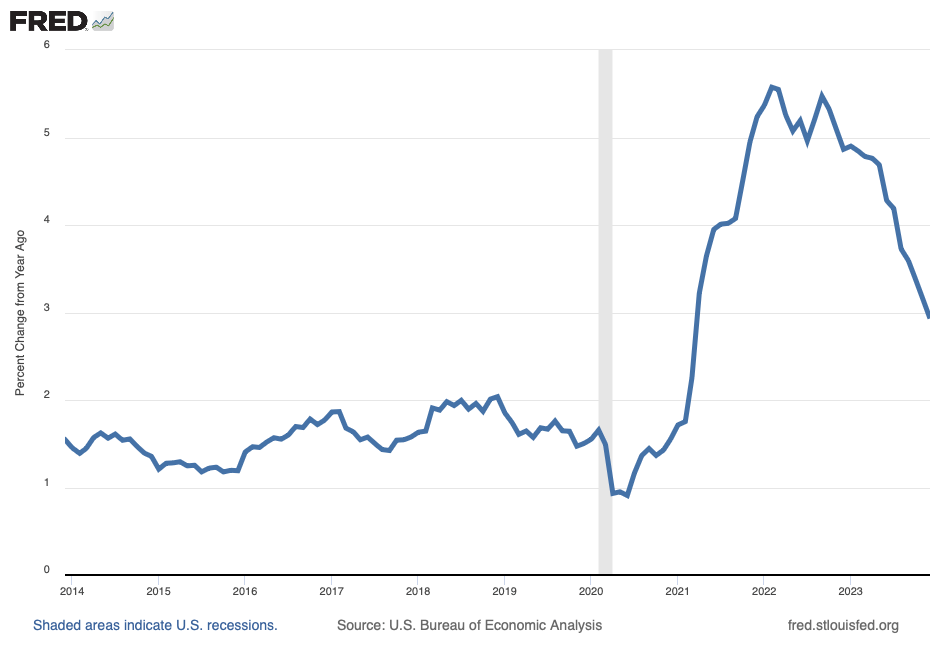

At any moment, the federal funds rate reflects the so-called stance of monetary policy: expansionary—and a relatively low federal funds rate—if output is below potential or inflation is below the two-percent target rate; or contractionary—and a relatively high federal funds rate—if output is above potential or inflation is above the two-percent rate. Currently, the stance is contractionary because inflation, which I Illustrate in Figure 2, remains elevated, though much less so than during 2022 and 2023.

Then, on Friday, everyone heard the Labor Department released its jobs report for January, during which employers added 353,000 jobs, nearly twice the consensus estimate among economists. In Figure 3, I illustrate the monthly change in employment, measured in thousands of employed persons; the right-most bar measures the 353,000 reading for January.

Thus, by the end of the week, everyone was talking about macroeconomics: the FOMC decision and the employment report, which, incidentally, seemed to corroborate the FOMC decision: a strong labor market favors a contractionary monetary policy stance, after all.

And then there was the bit about balance-sheet runoff, which almost no one heard.

Also on Wednesday, during a Federal Reserve press conference following the FOMC meeting, Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell indicated the central bank would, in the parlance of monetary policy, continue to shrink its balance sheet—more on the (nearly literal) metaphor in just a bit. In the statement the FOMC issued after its meeting, the committee indicated in part:

In support of its goals, the Committee decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 5-1/4 to 5-1/2 percent. In considering any adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will carefully assess incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks. The Committee does not expect it will be appropriate to reduce the target range until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 percent. In addition, the Committee will continue reducing its holdings of Treasury securities and agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities, as described in its previously announced plans. The Committee is strongly committed to returning inflation to its 2 percent objective. (Emphasis added.)

Federal Reserve Open Market Committee statement issued January 31, 2024.

The reduction of Federal Reserve holdings of U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed securities to which the FOMC refers in the statement is the so-called runoff, the dollar amount of securities subtracted from—or runoff—the balance sheet; a process the Federal Reserve deems necessary because the balance sheet of the central bank totals roughly $8 trillion, or roughly 28 percent of nominal GDP—an exceptionally high share of GDP. The comparable figure before the financial crisis was roughly $900 billion, or roughly 6 percent of nominal GDP.

How does a central bank balance sheet expand and contract, and why should anyone care?

As devoted Schooled readers know, the defining feature of a central bank is it issues the economy’s monetary base. In the United States, the monetary base primarily includes Federal Reserve notes circulating outside the banking system as currency—think, 1-dollar or 20-dollar bills, for example—and bank reserves in the physical or virtual vaults of banks; the vast majority of bank reserves are in virtual vaults. Importantly, to the Federal Reserve, the monetary base is a liability (which is owed, whereas an asset is owned). Meanwhile, to everyone else—including households, firms, governments (ours and those of other countries), and even other central banks—the U.S. monetary base is an asset: you and I own our U.S. currency; banks own their reserves, and so forth. In similar fashion, Japan’s (yen-denominated) monetary base is a liability of the Bank of Japan, the United Kingdom’s (sterling-denominated) monetary base is a liability of the Bank of England, and so on.

Consider, for example, the simplified Federal Reserve balance sheet I depict in Figure 5, where the monetary base appears as the sum of currency in circulation and bank reserves, both in the upper-right side of the balance sheet in Figure 4.

Unlike the balance-sheet accounts that comprise the monetary base, a liability, the remaining accounts in Figure 4 are entirely relatable: securities are mostly IOUs from the Treasury (which is distinct from the Federal Reserve), mortgage-backed securities (MBS) are essentially IOUs from households who borrow (from commercial banks, not the Fed) to purchase a home, and discount loans are typically last-resort IOUs from banks. Thus, assets on the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve are comprised largely of accounts receivable—think, payments due to the Fed from others. Federal Reserve equity, paid in by member commercial banks, is a source of funds. In similar fashion, you and I would place accounts receivable in asset accounts; and household equity is a source of household funding.

Because the accounts on each side of a balance sheet must sum to a common amount, we can understand quite a bit about monetary policy—including how a central bank balance sheet expands and contracts—by thinking about monetary-policy operations in the context of Figure 4. Suppose, for example, the Federal Reserve endeavors to decrease bank reserves (in order to raise the federal funds rate, say, as the central bank has done for about the last two years). To do so, the Federal Reserve could sell government securities, thereby decreasing the liability account, Bank Reserves, and decreasing the asset account, Securities, by a common amount. This is an example of a so-called contractionary open-market operation, which, incidentally, shrinks the central bank balance sheet.

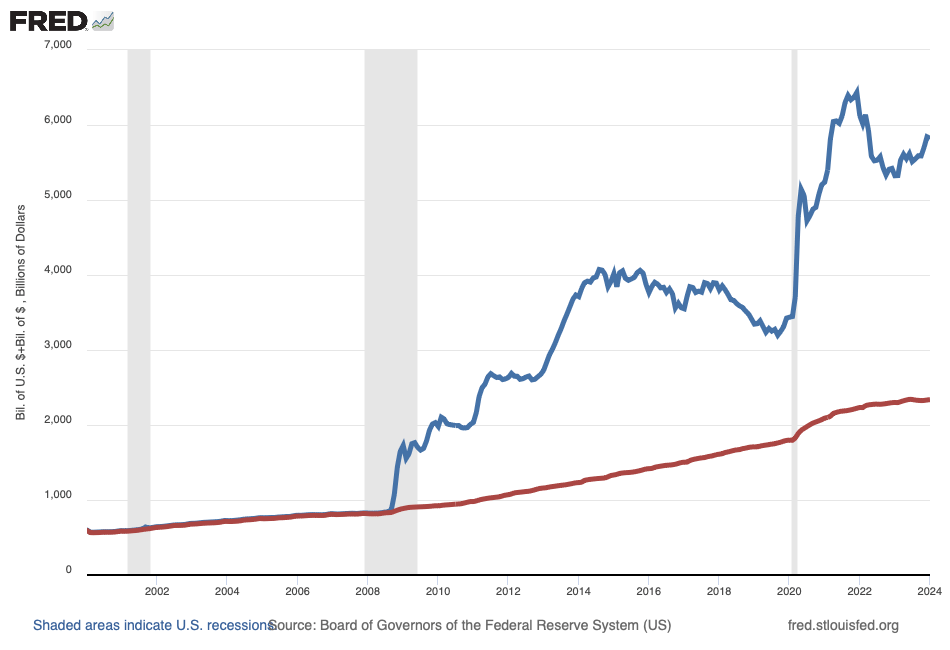

Put differently, then, expansionary [contractionary] monetary policy implies expanding [contracting] the dollar value of the balance sheet of the central bank. This is because expansionary [contractionary] operations generally increase [decrease] bank reserves and a corresponding asset, such as securities or MBS, for example. Nevertheless, over time, operations associated with conventional monetary policies change the monetary base relatively little—just enough to keep the federal funds rate in the target range, essentially. Meanwhile, operations associated with unconventional monetary policies, including large-scale purchases of government securities and MBS independent of the federal funds rate target or the stance of monetary policy, potentially change the monetary base dramatically. In Figure 5, I illustrate the U.S. monetary base (in blue) from January 2000.

Since the financial crisis in 2008 and to an even greater extent during the pandemic, the Federal Reserve has engaged in unconventional monetary policy, which has dramatically expanded the balance sheet of the central bank. In Figure 5, bank reserves (blue minus red) are barely visible before the Great Recession and the concomitant and unprecedented rise in bank reserves. Meanwhile, the rise in currency in circulation is a gradual, largely uneventful process—altered a bit during the pandemic—and driven by our steady demand for cash, literally. In December 2007, just prior to the Great Recession, the monetary base totaled $827 billion; in January 2024, the monetary base totaled $5.8 trillion, of which $3.5 trillion was comprised of bank reserves.

Unconventional monetary policy is often theoretically founded on the notion that markets—in this case, credit markets—are in some ways segmented: to take a simple example, suppose the short-term and long-term U.S. Treasury markets are segmented; this means an excess supply of loanable funds in the secondary market for short-term U.S. Treasury securities, say, does not flow to the secondary market for long-term U.S. Treasury securities, where suppose there is an excess demand for loanable funds. In such cases, secondary loanable-funds markets, such as the U.S. Treasury market in my example or a mortgage-backed-securities market, may require either so-called credit easing or quantitative easing—a difference in terms without a distinction, some may argue. Both terms refer essentially to large-scale open market purchases of securities. When the central bank conducts open market operations to target markets for specific securities (which the central bank books as an asset), the term credit easing appropriately describes the operations; whereas when the central bank conducts open market operations to target the quantity of bank reserves (which the central bank books as a liability), the term quantitative easing appropriately describes the operations. Or, put another way, credit easing intentionally alters the composition of central bank assets; quantitative easing intentionally alters the amount of bank reserves.

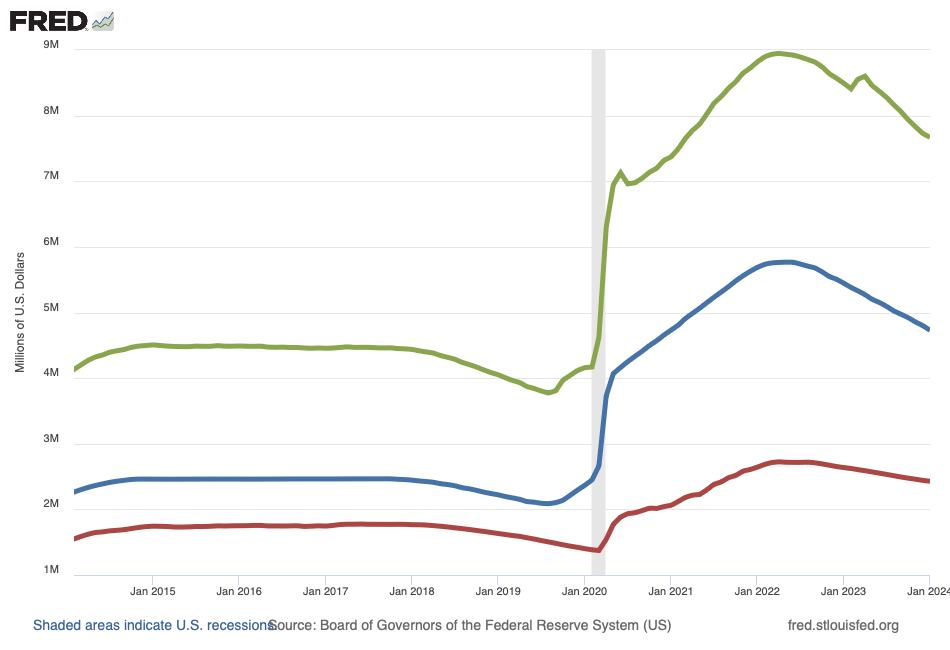

The argument for unconventional monetary policy is that, independent of the levels of interest rates in some credit markets, such as the federal funds market that the Federal Reserve targets or the short-term U.S. Treasury market, in some circumstances credit markets more generally may require a market maker or, in effect, a lender of last resort, a counter-party capable of buying a security when few others will. On multiple occasions since the financial crisis in 2008, the Federal Reserve has saw fit to engage in unconventional, expansionary monetary policy, causing the balance sheet of the central bank to expand dramatically. In Figure 6, I illustrate three features the Federal Reserve balance sheet: namely, the value of total assets (green), the value of U.S. Treasury securities (blue), and the value of mortgage-backed securities (red); the unconventional, expansionary monetary policy the central bank initiated during the pandemic is obvious.

Also obvious in Figure 6 is the runoff since January 2022, illustrated by the steady fall in all three balance-sheet measures. Interestingly, executing the runoff is a passive process. Each month, the central bank collects, from inside the economy, principal and interest payments due on U.S. Treasury securities and MBS. When the central bank collects principal payments, securities and bank reserves fall or, as it were, runoff the balance sheet one-for-one with the dollar value of the principal payments the central bank collects. As of now, each month the central bank allows $60 billion of U.S. Treasury securities and $35 billion of MBS to runoff the balance sheet. On Wednesday, Chair Powell indicated the runoff would continue, signaling the central bank would continue to pair conventional, contractionary monetary policy—think, targeting a federal funds rate between 5.25 and 5.50 percent, say—with unconventional, contractionary monetary policy—think, the runoff.

On the one hand, Chair Powell’s announcement that the runoff would continue was a bit of “nothing to see here.” After all, the runoff was going according to plan; in 2022, the FOMC announced:

To ensure a smooth transition [of the shrinking of the balance sheet], the Committee intends to slow and then stop the decline in the size of the balance sheet when reserve balances are somewhat above the level it judges to be consistent with ample reserves.

Federal Reserve Open Market Committee statement issued May 4, 2022.

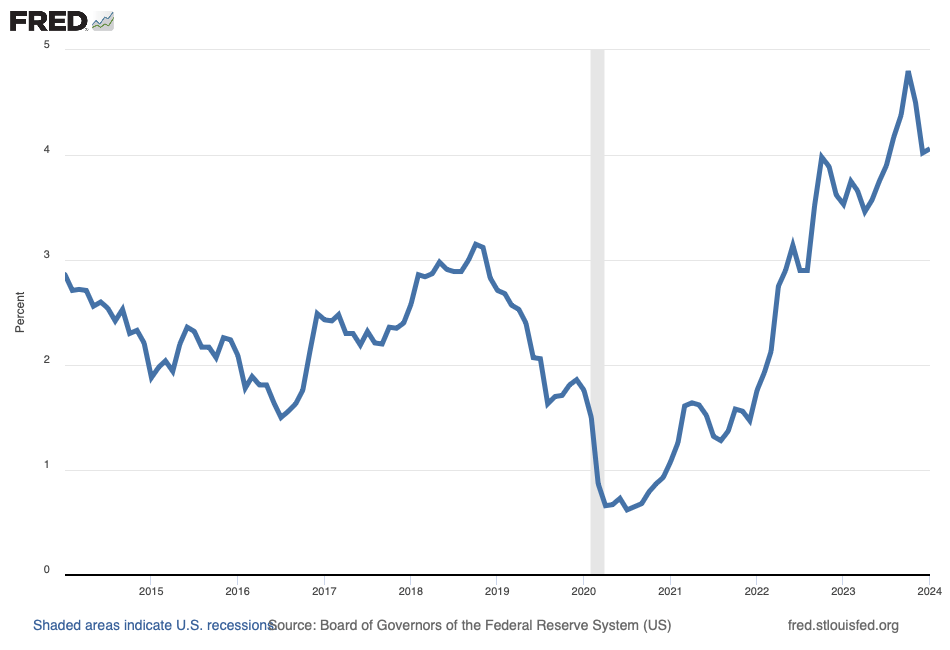

On the other hand, “consistent with ample reserves” is intentionally ambiguous. No one outside the Federal Reserve—and, I suspect, no one inside the Federal Reserve—could define “ample.” Presumably, we will know it when we see it. Thus, those wishing for a dovish tone from Chair Powell last Wednesday could have wished for him to characterize the current level of reserves as ample, warranting an end to the runoff. He did not do so; and the bond markets did not hear him do so, loudly and clearly: after the FOMC meeting, U.S. Treasury bond yields to maturity rose dramatically (for a time), because bond prices, which move in the opposite direction of yields to maturity, fell. In Figure 7, I illustrate yields to maturity on the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond.

When the stance of monetary policy is contractionary and, thus, interest rates are relatively high or rising, current bond prices must fall (and yields, which I illustrate in Figure 7, must rise) to make these IOUs attractive to savers. When the central bank announces its plans to continue the runoff, interest rates rise all the more.

On balance, market participants and observers more generally interpreted the FOMC decision on Wednesday as accommodative, just not quite yet: the central bank plans to lower rates soon (and, thus, accommodate employment, say), but not as soon as its next meeting in March. Thus, the central bank struck a less-dovish tone than some investors had wished to hear. In the words of the FOMC, “The Committee does not expect it will be appropriate to reduce the target range until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 percent.” Nor does the committee expect it will be appropriate to end the runoff anytime soon. In my view, all things—conventional and unconventional—considered, the FOMC was (rightly) less accommodative, less dovish than most reasoned—heard?—it to be.