This blog post accompanies the SDPB Monday Macro segment that aired Monday, August 4, 2025. Click here to listen to the segment, recorded Friday, 8/1, before the announcement of change in leadership at the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Economists talk lots about labor-market conditions in the macroeconomy. And to do so, they use lots of terms—think, the rate of unemployment, the employment cost index, the rate of labor productivity, initial and continuing jobless claims, job openings, and labor turnover, for example.

As a rule, the terms describe empirical and mostly easy-to-observe features of the economy; at the very least, the terms are mostly easy to define. Take, for example, the rate of unemployment, which the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) defines as the percentage of the labor force—the sum of employed and unemployed individuals—that is unemployed; unemployed individuals are without a job, actively seeking a job, and available to accept a job, by definition. On Friday (8/1/2025), for example, the BLS reported the rate of unemployment registered 4.2 percent in July.

Easy peasy, no?

No, not quite.

The term full employment is an important exception to the rule.

Full employment corresponds to a so-called natural rate of unemployment, which, by definition, persists over the long run, when economic output has reached its potential level.

Full employment is important, because the concept of full employment informs how we assess real economic performance and what, if anything, macroeconomic stabilization policies should do about it. Consider, for example, the Federal Reserve’s monetary-policy dual (Congressional) mandate of stable prices—and, thus, low and stable inflation—and maximum employment—and, thus, output at or very near its potential or full-employment level. Understanding the term full employment is fundamental to implementing sound monetary policy and much else. (For more on the dual mandate, see the Monday Macro segment, “Mind the Gaps.”) To know whether the rate of unemployment is high or low, we must know the natural rate of unemployment—the rate that persists when the economy has achieved full employment, a labor-market north star, as it were.

Full employment is exceptional, because unlike, say, the rate of unemployment, full employment describes a counterfactual feature of the economy that exists when economic output has reached its potential level, which we cannot observe. Interestingly, the way macroeconomists define the term full employment depends on the theoretical framework we use, the methodological approach we take, and the macroeconomic focus we choose when we conceive of the macroeconomy in counterfactual terms.

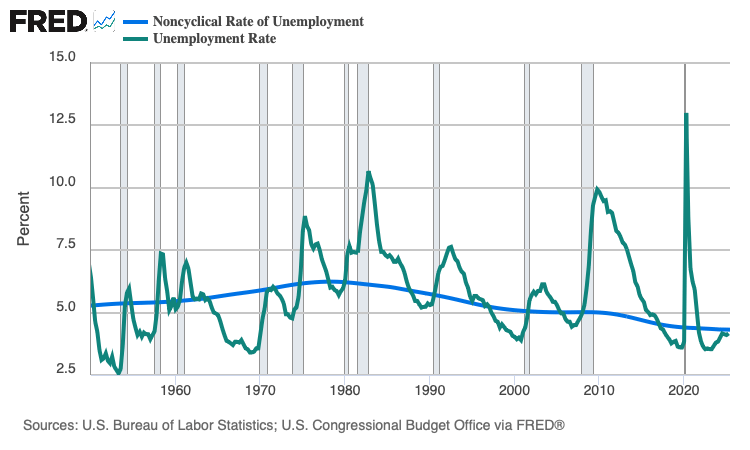

In Figure 1, I illustrate the actual unemployment rate (green) and a measure of the counterfactual natural rate; the reason FRED chose the term, Noncyclical Rate of Unemployment, for its measure of the natural rate of unemployment will be evident in what follows.

According to Figure 1, the actual rate of unemployment seems to revert to the natural rate in the long run: over time, the green line hovers above and below the blue line. In the second quarter of 2025, the actual rate (of 4.2 percent) registered slightly below the natural rate (of 4.3 percent), indicating the U.S. economy was operating very near its full-employment level.

So, how do macroeconomists think about full employment or, correspondingly, the natural rate of unemployment? Let’s count the ways—specifically, three ways for the purposes of the blog post.

Decompose the natural rate.

The most basic way to think about the natural rate of unemployment is to decompose the rate of unemployment into cyclical, frictional, and structural rates; then, define the natural rate of unemployment as the sum of the frictional and structural rates, only. Put differently, define the natural rate of unemployment as the actual rate of unemployment when the cyclical rate is zero. The cyclical rate rises as economic output falls below its potential level, as it does when the economic business cycle enters a recession. Thus the reason FRED chose the term, Noncyclical Rate of Unemployment, for its measure of the natural rate of unemployment I illustrate in Figure 1.

Essentially, macroeconomists reason frictional and structural rates of unemployment are natural in the narrow sense that frictional and structural unemployment exist independently of the (irregular and short-run) business cycle. Searching for a job opening creates frictional unemployment, which economists expect in a dynamic, free-enterprise economy. Types of skills and types of jobs are both heterogeneous, so matching skills to available jobs takes time and effort. And waiting for a job to open creates structural unemployment, which economists attribute to wages set above market-clearing levels (because of collective-bargaining power or market imperfections such as asymmetric information between demanders and suppliers of labor, for example). In the case of structural unemployment, the quantity of labor supplied exceeds the quantity of labor demanded no matter how hard unemployed individuals search for job openings; for the economy as a whole, searching does not reduce structural unemployment in principle.

Thus, decomposing the rate of unemployment yields a natural rate of unemployment—think, full employment—equal to the sum of frictional and structural rates of unemployment.

Consider a Beveridge.

As in William Henry Beveridge (1879 – 1963), the British economist who wrote extensively on labor markets, the social security and welfare systems that undergird them, and the government’s duty to achieve full employment. Most economists remember Beveridge for his work on the relationships between job vacancies (a measure of labor demand) and unemployment (a measure of labor supply). Economists later extended the analysis in the context of the (inverse) relationship between unemployment rates and job vacancy rates. (For more on Beveridge and the so-called Beveridge curve, see the the Monday Macro segment, “In Search of a Beveridge.”)

The Beveridge framework inspired a conceptualization of the labor market in a natural steady state, where the flow of individuals into employment equals the flow of individuals into unemployment, yielding a natural steady-state rate of unemployment. To understand the conceptualization, define the rate of unemployment as the number of unemployed individuals divided by the labor force, as follows.

For example, suppose the labor force includes 150 million individuals , of whom 7.5 million are unemployed

. In this example, the unemployment rate is 5 percent, or 7.5 million divided by 150 million.

The natural rate of unemployment is determined by the long-run rates of job finding and job separation

, which are driven, in part, by labor-market institutions, including government policies—think, subsidizing the unemployed or mandating a minimum wage for the employed, for example. The unemployment rate equals its natural rate when the number of unemployed individuals who find jobs at the long-run job-finding rate is equal to the number of employed individuals

who separate from jobs at the long-run job-separation rate, as folllows.

Substituting the long-run equilibrium relationship into the unemployment-rate relationship yields the natural rate of unemployment , as follows.

According to the expression, the natural rate of unemployment falls [rises] as the long-run job-finding rate (f) rises [falls] and as the long-run job-separation rate (s) falls [rises]. Depending on the causes, changes in job-finding and job-separation rates can affect frictional or structural unemployment rates, and thus the natural rate of unemployment. For example, a job-search training program—whether publicly or privately run—raises the job-finding rate and, thus, lowers frictional unemployment (and thus the natural rate of unemployment); whereas a (binding) minimum or efficiency wage lowers the job-finding rate and, thus, raises structural unemployment (and thus the natural rate of unemployment).

Thus, extending the Beveridge framework yields a natural rate of unemployment—think, full employment—as a steady state, where the flow of individuals into employment equals the flow of individuals into unemployment.

Conjure NAIRU.

In 1958, Alban William Phillips, then a professor at the London School of Economics, published, “The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861-1957.” Controlling for large increases in import prices, Phillips concluded statistical evidence supported the hypothesis that relatively low [high] rates of unemployment drive relatively high [low] rates of change of money wages. The evidence inspired the Phillips curve: the supposed trade-off between the rate of unemployment and the rate of inflation. The Phillips-curve trade-off almost immediately gained international acclaim. To many, the curve represented a policy menu of rates of unemployment and inflation; ostensibly, the policy maker could shift aggregate demand—by changing the interest rate, say—to achieve any combination of rates of unemployment and inflation represented by the curve. (For more on the Phillips curve, see the the Monday Macro segment, “Revolutions.”)

Sound too good to be true? It was.

According to the classical (real-nominal) dichotomy, the trade-off between the rate of unemployment—a real variable—and the rate of inflation—a nominal variable—is not permanent; indeed, the trade-off is, for all practical purposes, nonexistent. If anything, it lasts only until prices and wages adjust to the policy-induced inflation; and the time length of this adjustment is determined by how individuals—employees and employers, for example, who negotiate wages with inflation rates in mind—formulate expectations of inflation. The rise in the rate of inflation does not persistently affect the economy’s real features, including the real wage, the level of employment, and the rate of unemployment, which is driven ultimately by the rates of job finding and job separation that determine the levels of frictional and structural unemployment.

If we assume individuals are rational, then individuals formulate expectations of the inflation rate (and all else) using all available information; moreover, individuals interpret the information based on an accurate understanding of their complex economic environment. A policy-induced inflation will accelerate the rate of inflation, but leave the rate of unemployment no lower than its natural rate. Thus, full employment describes the lowest rate of unemployment consistent with stable (non-accelerating) inflation. The full-employment or natural rate of unemployment is the NAIRU: non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment.

Thus, conjuring NAIRU and thus, the Phillips curve, yields a natural rate of unemployment—think, full employment—where the rate of inflation is nonaccelerating.

It’s good to have a point of view.

Macroeconomists study the economy as a whole. As such, we are most interested in the general features of the economy—measures of aggregate quantities and average values that pertain to the central tendencies of aggregate economic activities. For obvious reasons, the unemployment rate is an important general feature of the economy. Essentially, we want the unemployment rate as low as possible, but not too low. Achieving the optimal outcome requires we know—or at least we have a reasonable, informed point of view of—full employment and its corresponding natural rate of unemployment, where the macroeconomy lives its best life.

How macroeconomists define and talk about the term full employment depends on how they conceive of the macroeconomy in counterfactual terms. Whether we think about the natural rate in the context of frictional and structural unemployment (think, decompose the natural rate), a steady-state of flows into and out of employment (think, consider a Beveridge), or a nonaccelerating inflation rate of unemployment (think, conjure NAIRU), a common theme is evident: market structures and the institutions governing them determine full employment, for better or worse. Conversely, macroeconomic stabilization policies—including monetary policies of the sort we debate often and vigorously—do not determine full employment.

The current debates about and tensions around optimal monetary policy—whether the Federal Reserve should lower its target for the federal funds rate, for example—demonstrate the need for a reasonable, informed point of view about full employment. And while everyone is entitled to a point of view about whether the economy has reached full employment, no one is entitled to a point of view about whether macroeconomic policy should raise full employment, because that’s not how any of this works.